|

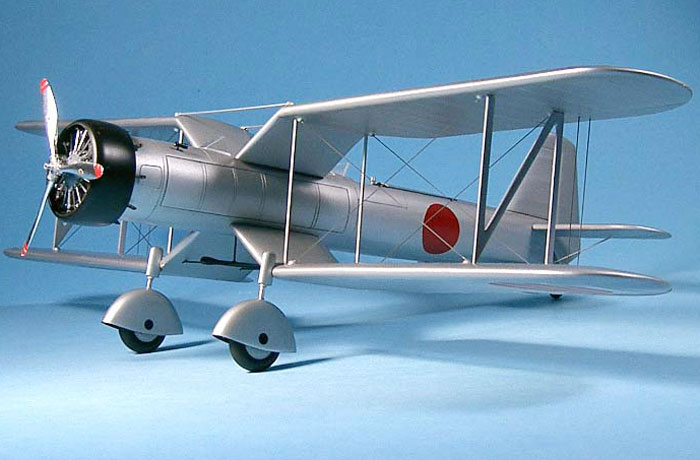

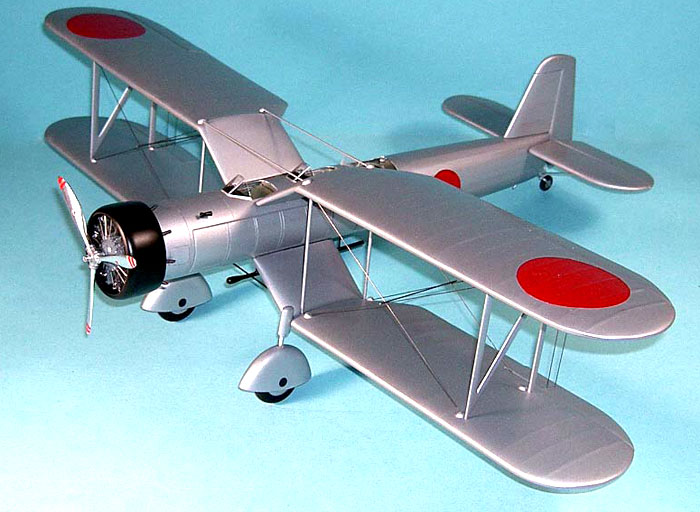

1/32 scale Nakajima B4N1

or

How to Scratch-Build a Model Having Only One Photo and No Text

|

|

|

Nakajima B4N1 |

by Frank Mitchell

HyperScale is proudly

sponsored by Squadron.com

Note to Rivet-Counters (You know who you

are): Reading this article could bring on cardiac

palpitations, sweating, and significant anxiety. My considered medical

advice would be to take two aspirins, go read something that provides

great detail on a 109 or something, and call me in the morning.

This model had a long gestation period, in fact,

close to 30 years.

In the early 1970s, Bob Mikesh gave me a picture of

an experimental Japanese torpedo aircraft dating from the 1930s. He

thought it would make an interesting model and would try to get further

information. In the early 1970s, Bob Mikesh gave me a picture of

an experimental Japanese torpedo aircraft dating from the 1930s. He

thought it would make an interesting model and would try to get further

information.

Over the next 10 or so years, he, Lloyd Jones, and a few

other people all tried to come up with more, but that one photograph

(see pictures) is all that could be found. At one point, in the

mid-1980s, Bob asked a friend of his in Japan to see what he could do,

and the friend drew up a three-view drawing, but was able to add very

little additional information.

Both Bob and I saw all kinds of problems

with the drawings, so back into the file cabinet it went. In early

January this year, I ran across the file and decided that if anything

was ever going to be done, it needed to happen before I got too old to

see the parts.

I knew the aircraft’s designation and that it was a

one-off in 1932. I also knew its basic dimensions, that it was a

three-place torpedo bomber, and that it was underpowered. Since no other

photos had ever turned up, that was about it. (Until, of course, this

article appears, at which point I will receive 47 contemporary detailed

photos and drawings including the color of the test pilot’s shorts.)

However, the shape of the thing was so intriguing that, after a few

telephone conversations with Bob, I developed a set of drawings of my

own incorporating what little we knew, and the small bits of information

that had surfaced over the years.

There is obviously a fair amount of conjecture in

the model, but it is truly amazing what one can determine from one

photograph if you have the help of some very knowledgeable people.

The model was built pretty much in my standard way,

but because of the unique shape of the wings, they received priority

because unless they worked, there wouldn’t be any point dealing with the

rest. The photos will help to illustrate everything.

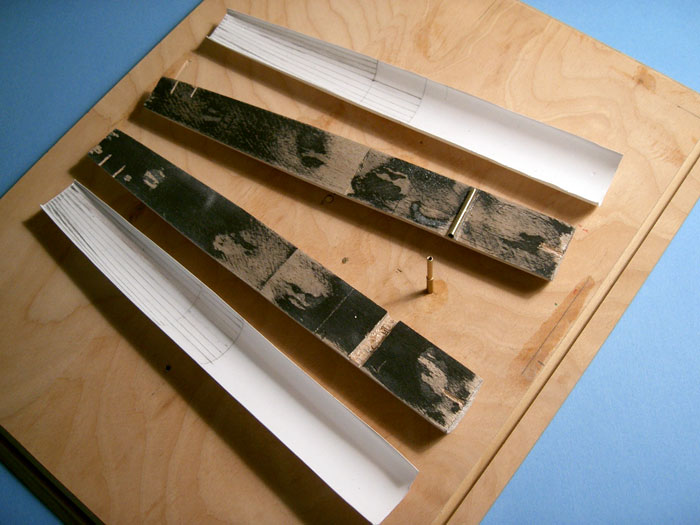

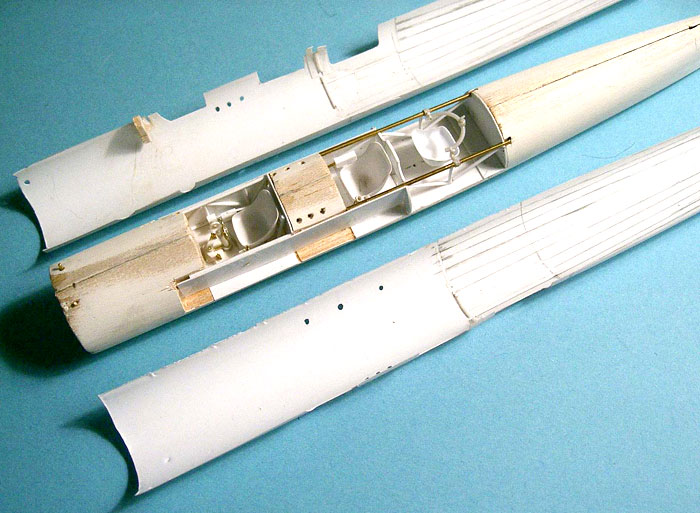

The first step was to prepare molds for the wings,

tail, cowling, and fuselage.

I carved four wings, because having the balsa

inside the plastic outer skin would make for much stronger attachments

to the fuselage and for the struts. The tail was done in basswood in two

pieces, the stabilizer and fin/rudder. The fuselage was composed of four

pieces: the forward section (from about the middle of the gunner’s

cockpit to the nose) was turned from balsa on a small lathe while the

rear portions were carved. The parts for each side were glued together,

but the two halves were not joined until later. The cowling was turned

from basswood.

All the parts were vacuum-formed in styrene, after

which they were cut from the plastic and the edges sanded to get as good

a match as possible. The balsa fuselage molds were then glued together.

Click

the thumbnails below to view larger images:

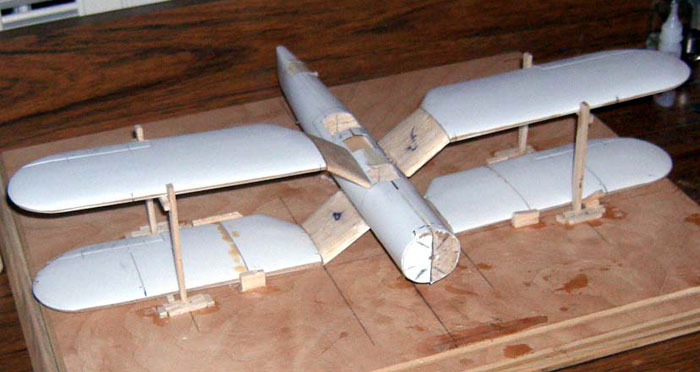

The next step was the building of the jig/building

board that is visible in a number of the photos. Although a jig is

useful in most any major conversion or scratch-building project, it was

essential in this one. There is no other way I could see of getting

those x-wings lined up and square without one.

Each wing root was made from two pieces of balsa

sheet. Each piece had grooves filed that would carry a piece of plastic

tubing through which brass wire would be placed. This wire went into

holes in the wing and the fuselage. A fair amount of time went into

making sure that the wings would be square to the fuselage, and that the

wings were correctly spaced and even. Scrap pieces of balsa were glued

to the jig to make sure that the wings would be properly spaced no

matter how many times I had to put them in or take them out of the jig.

Once I was satisfied with the wing placement, the N-struts and smaller,

inboard straight struts were made and fitted. The final pieces here were

two small brass struts that run from wing to wing above the cockpits.

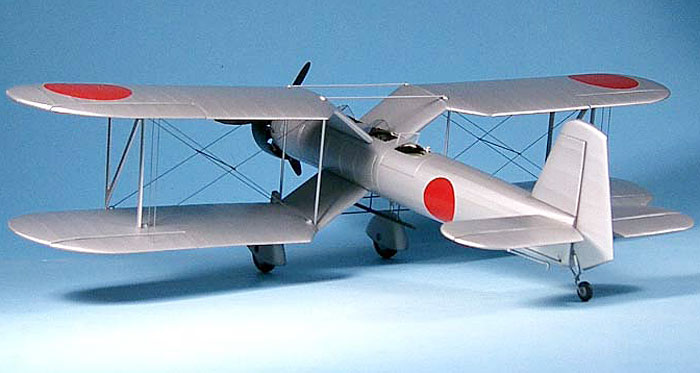

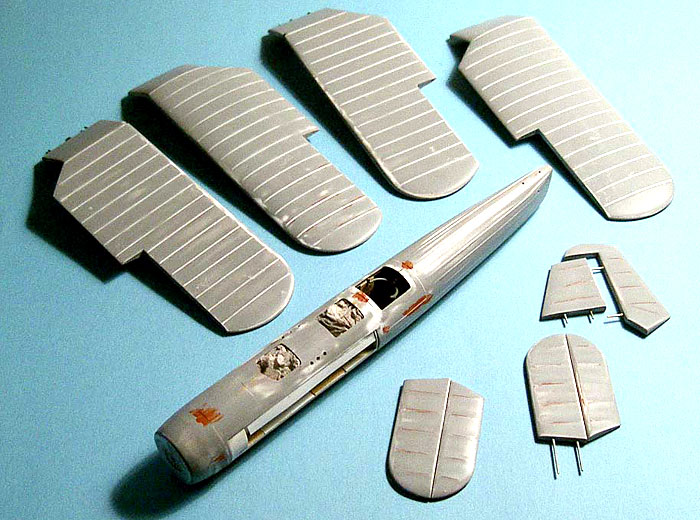

The ailerons on all four wings were then cut out

and pinned with brass wire.

Since I couldn’t make much further progress without

the fuselage being more complete, it was removed from the jig and the

interior detailing began. Nothing much exciting, just working one’s way

through all three cockpits taking my best guess as to what they

contained, with some help from some Maru Mechanics covering

similar-vintage Japanese aircraft.

Click

the thumbnails below to view larger images:

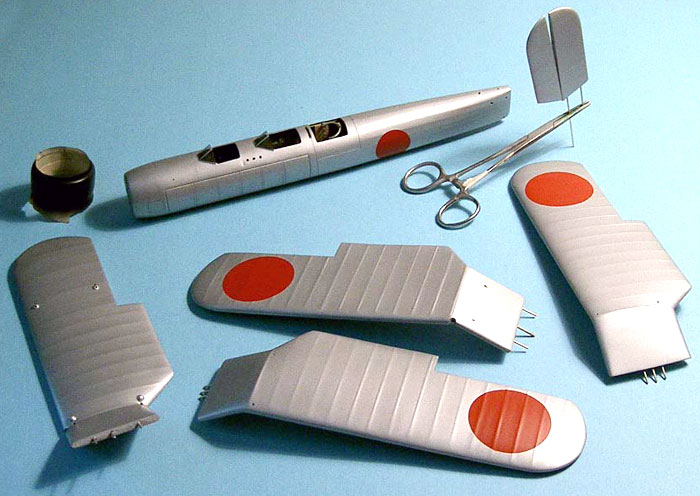

Once that process was complete, the tail surfaces

had their plastic coatings added, and as with the wings, all movable

surfaces were cut apart and pinned with brass wire. The fixed portions

were then fitted and pinned to the fuselage with the aid of the jig.

They would not be glued until painting was complete.

The semi-external fuel tanks run along the sides of

the fuselage. These were done by simply cutting those areas from the

fuselage sides. The cut pieces will be replaced in their openings after

some sanding and scribing are carried out.

I used a Williams Brothers engine and a propeller

stolen from a 32nd Oscar kit.

The main landing gear had its own set of problems

in that it is mounted on the leading edge of the wings at the angle

where the inverted gull stops. Molds were made for the right and left

sides of the large wheel fairings and these were formed using

heat-and-smash. These were assembled around a horizontal, shaped piece

of 1/8th balsa. This would contribute strength as well as a

handy place to mount the wheel. The wheel (singular) was found in the

scrap box. It was cut in half so that the two halves could be glued onto

the balsa inside the fairings. The struts and their associated mountings

were made up from brass and aluminum tubing; notches and holes were

placed in the wing to mount the completed gear.

The tail wheel was also found in the scrap box and

its struts were also made up from brass wire and tubing.

There is a structure under the fuselage which I

assumed was a mount for the torpedo as well as horizontal struts running

from wing-to-wing. That made sense because they would match the two on

the upper wing above the cockpits. Brass wire and a piece of plastic

sprue were used to make all this.

At this point, everything was shot with automotive

lacquer primer and the usual routine of priming, sanding, puttying, and

priming began and continued until I was happy.

Although I have tried a number of ways to simulate

fabric covering, I tend to come back to the long and messy method I used

here. That is the application of very thin and narrow strips to the

surface, then apply putty along the edges of each strip. This is

followed by sanding, mostly with the fingertips; the sanding is done in

two stages: First, it is chord-wise, between the strips, and that

is followed by sanding across the strips, again using the tips of

the fingers. The result is a series of “ribs” and “stringers” with only

a small “indentation” between them, which I think gives a fair

representation. A small amount of scribing was done on the metal areas

of the fuselage and the gas tanks.

After this was accomplished, some details needed

attention:

·

The landing hook was made from brass wire, as were two

struts that run between the tops of the upper wings.

·

The individual exhaust stacks were made by gluing

extensions to the pipes provided by the Williams Bros kit so that they

protruded from the cowling the correct distance.

·

18 small protrusions (made by heating-and-smashing over a

round mold) that cover the insert point of each flying/landing wire were

added to the wings very near to the attachment point of the wing

struts. Four others were made to cover the attachment point of the two

upper horizontal struts running between the wings.

·

The windscreens were molded from clear vinyl over a simple

wooden mold (front two), and a flat piece of plexiglass (rear).

After a final coat of primer, the model was shot

with an old faithful brew I have used for years.

It is made by throwing

a bottle of Testor’s flat aluminum into a larger jar and adding about

equal amounts of Floquil Flat finish and lacquer thinner. It is made by throwing

a bottle of Testor’s flat aluminum into a larger jar and adding about

equal amounts of Floquil Flat finish and lacquer thinner.

These

proportions vary with my mood, but if the humidity is low, I might throw

in a little more Flat Finish.

Gives a very nice even finish.

The

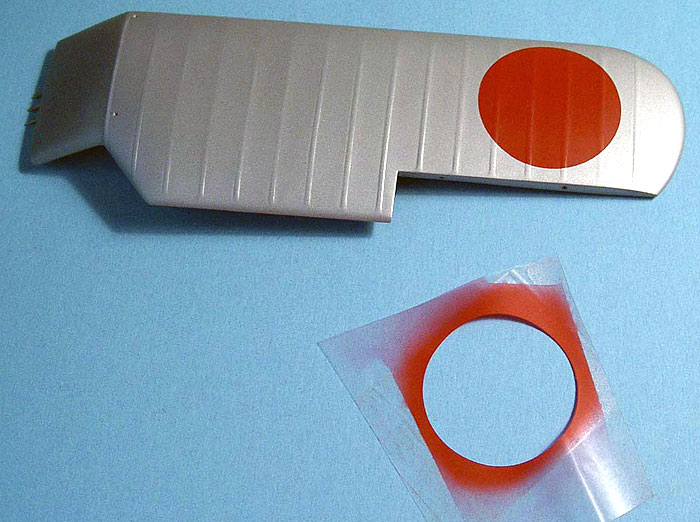

national markings were sprayed on using masks of prepared frisket.

After all this, the whole thing was covered with a fairly generous spray

of the Floquil Flat Finish that had only a small amount of lacquer

thinner added. The only decals are black circle covering what I assume

are axle access doors on the wheel pants.

The prop was covered with aluminum foil and the

backs of the blades were painted flat black.

It is always interesting and (and very satisfying)

that, after all that work, final assembly usually only takes a couple of

hours. In this case, most of the time was spent on the flying/landing

wires. I used .015 stainless wire for those.

This was an interesting project. It combined the

efforts of others and a fair amount of guesswork plus a bit of trial and

error on the wing construction. It is also one more off the

“I-am-going-to-build-that-someday” list.

Model, Images and Text Copyright ©

2004 by Frank Mitchell

Page Created 03 June, 2004

Last Updated

03 June, 2004

Back to

HyperScale Main Page |

Home

| What's New |

Features |

Gallery |

Reviews |

Reference |

Forum |

Search