|

1/32 scale scratchbuilt

Federal Aircraft Factory (FAF)

N-20 Aiguillon

by Frank Mitchell

|

|

|

Federal Aircraft

Factory

(FAF) N-20 Aiguillon |

HyperScale is proudly

sponsored by Squadron.com

Did you ever build one of those models that fought

you every inch of the way? Well, this is one of them. Lots of re-making

of things that I screwed up, or glue going into the wrong place, or

having to paint the bloody thing twice, etc. Trust me, you are never too

old or too experienced to have these things occur, nor is it any less

frustrating. However, the fact that this model was actually built at all

is a tribute to the great people that inhabit the modeling sites of the

internet.

For example, one day, while avoiding doing something constructive, I

threw out a question asking if anyone had information on obscure Swiss

aircraft. I almost immediately heard from Mike Kirk, a Brit who has

lived in Switzerland for many years. He first disabused me of the idea

that the airplane is obscureóit isnít, in Switzerland. From then on, he

was a fountain of photographs and help, and I could not have done it

without his help. The good news, in fact, about this project is that

Mike kept sending lots of good pictures and information. The bad news

was that he kept sending me lots of good pictures, which meant that some

things had to be redone or modified as the later information became

available. There were a few cases (which I will not point out) where the

information was too late to be added without tearing the model apart,

but for the most part they were included. I had no idea so much

information about the N-20 was out there.

Background

For those of you who are, like I was, rather

ignorant of this airplane, the N-20 Aiguillon (Sting) was ordered in May

1948, and contained several very new features. Its four British-derived

Mamba turbofan engines were buried in the wing, and the cold air from

the fans were ducted through additional combustion chambers on each side

of the engine. This reheat device, which doubled the normal thrust of

the engines, was to be used mainly for take-off and combat. For short

take-off and landing, the secondary airflow could be deflected through

large slots on the upper and lower wing surfaces. When the lower slots

only were open, the deflected air acted as an aerodynamic flap; with

both systems in operation, the deflected air acted as a thrust reverser.

As a substantial proportion of the air flowed through about half the

wingspan, the aerodynamic drag of the relatively thick wing was very

low. To extend endurance, two of the four engines could be shut down in

flight.

Performance estimates included a maximum speed of 680 m.p.h. at 3,280

ft.; time from 3,280 ft. to 32,800 ft., 2 minutes; take-off run 760 ft.

and landing run 777 ft.

The N-20 was designed to have a detachable weapons-bay that could be

changed in 10 minutes. Alternative loads were 1,764 lb. of bombs, six

20-mm. cannon, four 30-mm. cannon, thirty-two missiles, cameras or

additional fuel. Two 20-mm. Cannon were permanently mounted in the nose.

Anticipating the F-111, the pilot was provided with a watertight escape

capsule, ejected by an 8,810-lb.thrust rocket.

Due to problems with its engines, development of the N-20 was cancelled

in 1952. It was not flown, although it did have a number of high-speed

taxi tests and, according to one source, actually did lift off for a

short distance.

The model is an excellent example of the old adage

that the simpler something looks, the more complex it can be. Although

the lines are lovely, the intakes, along with those curvy engine

fairings, the exhaust/bypass outlets, the cockpit, and the landing gear

all combine to make a difficult-to-capture-and-look-decent shape. As

usual, the pictures will show most of the construction, and probably

better than words.

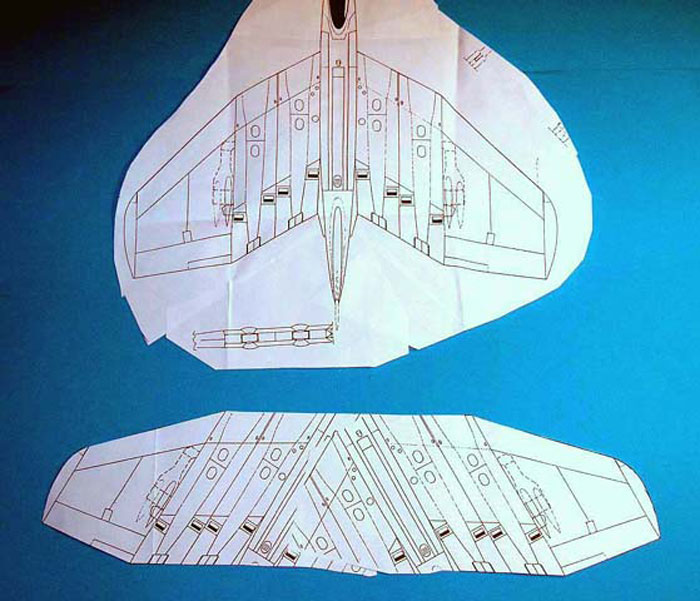

It seemed impractical and a lot of excess work to build the wing as it

is on the airplane, so the drawings were manipulated to make a straight

piece. It did mean constant checking to assure that everything would be

straight when the wings were finally cut apart, but it made life much

easier while getting there.

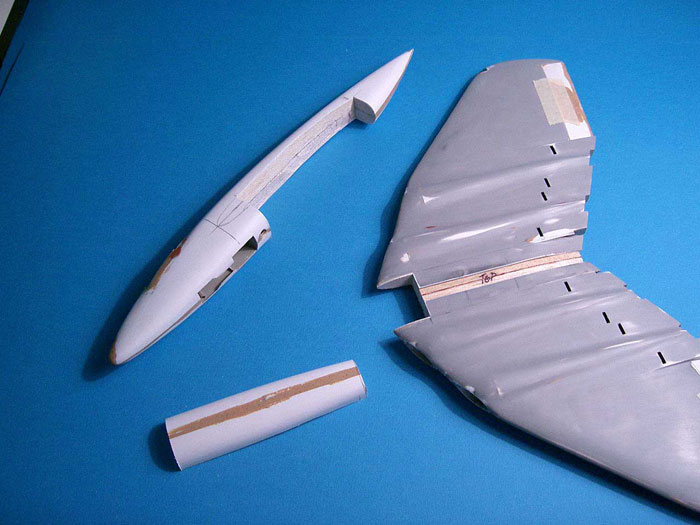

Once the basic wing was cut and sanded to shape it was formed using my

usual technique for big pieces, i.e., clamping the styrene in door

hinges and heating and smashing. The main wheel wells were cut into the

outer wings and the wells themselves made up from styrene sheet. The

skins were then attached to the wings with epoxy. Now the real fun

began.

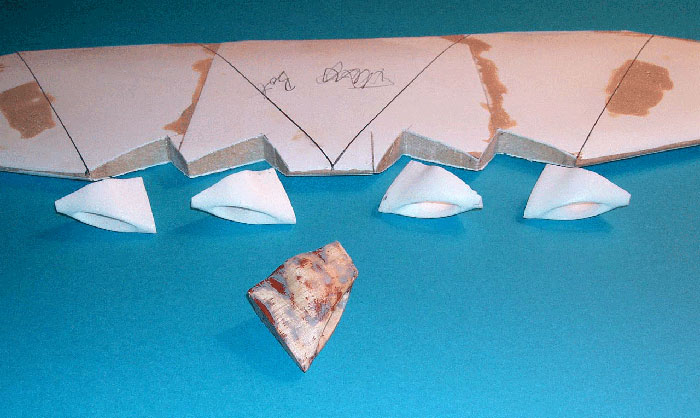

The first thing tackled were the intakes. After some thought, it seemed

that the easiest way to get identical, smooth intake surfaces inside and

out was to mold them from resin. In order to do that however, one needs

a mold. So, on a dull Saturday afternoon, I sat down with a chunk of

basswood and drilled, carved, and sanded away. 3 hours later, I had the

master seen in the pictures. A mold was made from RTV, and four intakes

were made. The appropriate openings were cut into the wing leading

edges, but before they could be mounted, I needed to find some engine

faces. They are close to the intake lips and very visible. After some

prowling through the backlog, I found some perfect ones in the exhausts

of a 48th S-3 Viking. I used one of those to make an RTV mold and did

four of them (This model was much like a ship in its need for

replication; that bloody wing needed either 4, 8, or 16 of everything).

Notches were cut into the wings so that the engine faces would be

equally spaced behind the intakes, but before they were glued into

place, the exhaust and fan outlet areas were built.

Click on the thumbnails

below to view larger images:

An section was cut from the wings the size of the

exhaust areas. The rest is probably easier seen in the pictures than

described in words, but basically the whole structure was built-up from

sheet styrene. Just couldnít figure out any other way to make sure

everything was open and visible they way it should be. Once complete,

the two sections were epoxied into the wings, as were the engines and

engine faces.

A simple mold was cut from balsa for the main engine fairings and eight

of them were heat-and-smashed, cut out, and glued into place on the top

and bottom of the wing. Now the entire wing was filled and sanded ad

nauseum until everything looked straight and smooth. The control

surfaces were cut from the wing, nav lights were put into place, and the

wing was ready for the dramatic moment of being cut apart and

reassembled at its proper sweep back angle. It was, and everything even

lined up properly. Amazing. Riding on that high, I (thankfully) put the

wing aside so that the fuselage could be attacked.

The fuselage was vacuum-formed over my usual balsa molds. The nose wheel

well was the first opening cut, and the well itself made up from sheet

styrene which was painted and detailed.

Click on the thumbnails

below to view larger images:

The cockpit opening was cut out and lined with

styrene sheet. The consoles were made from balsa and also covered with

thin sheet. The instrument panel was made in my usual way; a sandwich of

styrene backed with clear vinyl and having the instruments white-glued

to match the holes in the outer styrene. The control column was made up

from various bits and pieces of aluminum tubing and brass wire, and all

the usual cockpit detailing was added.

As an example of the earlier statement about this being a complex

project, the canopy, of all things, turned out to be a bit of a hassle.

For reasons that I assume had something to do with the escape capsule,

the N-20ís canopy is attached to a fairing that slides with it as it

opens. The fairing is rather thin and, to make life more interesting,

the canopy to which it attaches is entirely framed in clear plexiglass.

I could have just closed the thing and gone on with my life, but

cheaters never win, so after a bit of head scratching, my approach was

to carve a basswood mold for the windscreen/canopy and heat and smash

several vinyl copies. Then, on the mold itself, a line was drawn which

outlined the inside of the inner framework. One of the canopies was cut

down to that line, while another was cut to the overall canopy outline.

These were then (carefully) glued together with superglue, and the edges

sanded and polished. Next, the fairing was cut from sheet styrene and

glued to a spacer that was shaped to the bottom of the canopy. This

assembly was glued to the canopy itself, and epoxy was used to form the

final shape. Involved, but I couldnít think of any other way to do it.

The windscreen also had its problems, again caused by the ejection pod.

There is a clear plexiglass panel at the rear of the screen, covering

the area of the arch. From a modeling standpoint, that means that the

windscreen is a sealed chamber, and that the fit has to be decent or it

wonít look right (or good). This was tackled by taping the windscreen to

the fuselage and carefully measuring the distance between the bottom

edges. That was then duplicated off the model using tape to make the

windscreen have the same shape it would have on the finished model. The

arch was then traced onto cardboard and then onto clear vinyl, measuring

and shaping all the way. When the fit seemed to be reasonable, it was

glued using very small amounts of superglue while trying very hard not

to get my fingers as well. The completed windscreen was not actually

glued on until the last second before painting began.

Once that was finished, the fuselage was put on the building board and

the outline of the wing cross-section was drawn on its sides. That area

was removed, and the wing was fitted in place. It was not glued yet;

lots to be done before that took place.

Next up was the landing gear, since they are all three trailing link

designs, and were made from brass and aluminum tubing with a bit of

soldering and supergluing. There was also some basswood used for the

nose gear leg shape; it surrounded a piece of tubing that supplied the

strength. Other bits and pieces included some square aluminum tubing,

and some colored plexiglass (the bottom of the nosegear that was also

the pivot for the trailing arm). The wheels were cast in resin using for

masters a main wheel from an ancient Monogram TBM (main wheels) and

something from the discarded parts stash (nose gear). The gear doors

were built up from sheet plastic.

A mold was made for the small wheel fairings that are on the top and

bottom of the wing, and eight copies heated and smashed. These were cut

out and glued in place, although the bottom ones were applied in several

pieces as they were attached to the geardoors as well as the wing. The

relevant gear doors also had to be modified to reflect the fairing

shape.

Next came the weapons pod. Donít let anyone tell you that you canít mold

undercuts using a vacuum-forming setup. You can; it just takes a little

thought. The mold was carved and sanded from balsa and smoothed using my

favorite primer, Kilz. The mold was then vacuum-formed in the same way

as the other pieces of the model, just using care and patience to make

sure that the plastic is as warm as it will get, short of melting. Then

turn on the shop-vacuum, and quickly place the warm plastic over the

mold. I also use a pair of soft gloves to make sure the plastic has

followed the shape. The result can be seen in the photos. Note that this

really doesnít work very well with sharp-edged shapes, but in this case,

the curves of the pod did very well; a bit thin, but useable.

Click on the thumbnails

below to view larger images:

With all the main components built, it was time for

a little priming and sanding followed by scribing of panel lines,

hatches, etc. When that was finished (if it ever is), the wings were

glued into place, followed by the weapons pod, followed by the fin, with

lots of sanding, priming, and scribing taking place between each step.

Natural Metal Finish

The

airplane was in natural metal when it was tested, and that I what I

decided to do. I did cheat in one respect; I left off the nose test

probe. Looks much cooler that way. The

airplane was in natural metal when it was tested, and that I what I

decided to do. I did cheat in one respect; I left off the nose test

probe. Looks much cooler that way.

I used Alclad, masking off various panels using frisket. The control

surfaces, and other small parts were painted with varying shades of

Alclad and Testorís Flat Aluminum. As I said earlier, I completely

screwed up paint job #1 and, after letting the thing sit for a couple of

weeks, I sanded off all the old paint and started over.

Markings

The decals are few; the Swiss tail marking came

from a Hunter decal sheet, and the sweep spear was a combination of

paint (forward), and decal sheet (aft). The name was done by the simple

expedient of blowing it up to 8.5 x 11, and tracing it with the blackest

marker I could find.

When reduced to a little over an inch long, all the

jiggly lines disappeared and it was copied on to clear decal sheet. I

looked hard at all the pictures I had, but could not find any of the

tiny-written so common today. Either it was too small, or I missed it.

So anyway, it is (finally) finished, and it does make an intriguing

addition to the collection. For anyone coming to the Atlanta Nationals,

it will be on display; just donít look too close.

Click on the thumbnails

below to view larger images:

Model, Images and Text Copyright ©

2005 by Frank Mitchell

Page Created 01 June, 2005

Last Updated

01 June, 2005

Back to

HyperScale Main Page |

Home

| What's New |

Features |

Gallery |

Reviews |

Reference |

Forum |

Search