|

Supermarine Spitfire Mk.I

Bob

Laskodi

|

|

|

Supermarine Spitfire

Mk.Ia |

Tamiya's 1/48 scale Spitfire Ia

is available online from Squadron.com

The 63rd anniversary of the Battle of

Britain (BoB) is almost upon us, and it is an appropriate time to

remember those brave warriors in the air who paid the ultimate sacrifice

for their countries. This article pays tribute to one of the most famous

aircraft featured in the BoB; the Supermarine Spitfire.

On June 18 1940, aware of Hitler’s plan for the

invasion of Britain, Winston Churchill made his “Finest Hour” speech

calling to arms his fellow countrymen: “The Battle of France is over,

the Battle of Britain is about to begin, upon this battle depends the

survival of Christian civilization, upon it depends our own British life

and the long continuity of our institution and our empire”.

Historians often argue as to the exact dates that

the BoB was fought, however it is generally agreed that July 10 through

31 October 1940 are the most appropriate dates. The BoB was significant

in many ways, not the least of which, is that it was the first major

battle to be fought entirely in the air.

The BoB consisted of four major phases in support

of “Operation Sealion”, the proposed German invasion of the British

mainland. Phase 1 which ran from July through early August was

characterized by German attacks on the convoys supplying Britain in the

English Channel and Thames Estuary, attacks on industrial targets, and

large scale German fighter sweeps hoping to draw up the RAF for

destruction. Phase 2 featured “Adlerangriffe”, the Luftwaffe’s planned

destruction of the RAF on the ground and in the air, culminating in

“Adlertag” on August 13, one of the largest aerial battles ever fought.

Phase 3 featured a change in German strategy from destruction of RAF

targets, to the “Blitzkrieg” of London in early September, a change in

strategy that many historians argue cost the Germans victory in the BoB.

And lastly, Phase 4 starting in early October, the end of large-scale

day attacks with the majority of the fighting taking place at night over

large British industrial centers and cities.

PHASE 1:

Convoy Attacks & Fighter Sweeps

While 10 July 1940 is generally accepted by most as

the start of the BoB, there were many previous attacks by the Luftwaffe

on the British mainland. The Luftwaffe made its first large scale attack

on the night of 18 June, when a force of over 100 bombers attacked a

variety of targets between Yorkshire and Kent. A soon to be famous South

African named A.G. “Sailor” Malan shot down two German bombers from his

Spitfire that night when they were illuminated by searchlights, an

amazing feat of marksmanship. The following night, approximately 100

German bombers hit a variety of targets scattered throughout England and

Wales.

The Luftwaffe made its first daylight raid on 1

July, hitting targets in Scotland. This was followed by small-scale

daylight raids over the next three days, and combined day/night raids

through 9 July. Then on 10 July, the battle started in earnest.

On the morning of 10 July, a ship convoy code-named

“Bread” was transiting from the Thames Estuary to the Straits of Dover

when it was detected by a reconnaissance DO-17P of 4(F)121. This

aircraft was heavily escorted by BF109’s from I./JG51, and six Spitfires

from No. 74 intercepted. The Spits were heavily outnumbered by the 20+

BF109’s but managed to attack and damage the DO17, which eventually

crash-landed in France. The DO17 managed to alert the Luftwaffe and they

responded with over 70 aircraft to attack “Bread” later in the

afternoon. About 30 British fighters intercepted the German formation

and the first large-scale dogfight of the BoB ensued. A total of 6 RAF

and 13 German aircraft were lost in this engagement, but the most

significant fact of the battle was that only one ship from “Bread” was

lost. In addition, coincident with the raid on “Bread”, a strike force

of JU88’s hit Swansea and Falmouth. The British did not intercept this

attack. Further shipping attacks were accomplished on 11-18 July,

although generally poor weather hampered operations.

On 19 July weather improved and the B.P. Defiants

from 141 Squadron were patrolling in the English Channel. The Defiants

were jumped by over 20 BF109’s from III./JG51 and in the ensuing battle

six Defiants were lost while JG51 lost only one BF109. The carnage may

have been worse had not 111 Squadron arrived on the scene to ward off

the BF109’s. This battle illustrated the weakness of the Defiant against

the far superior BF109 and along with another disastrous engagement in

August led to the withdrawal of the Defiant from day operations.

Further small scale convoy attacks and fighter

sweeps continued throughout the month, and the Luftwaffe aces suffered

some heavy losses when Noacke, von Houwald, Erlich, Riegel, and Keidel

were lost and leading German ace Werner Moelders was shot down and

wounded.

A combination of poor weather, and German

preparations for “Adlertag”, the all out assault of the RAF in the air

and on the ground led to lower levels of combat activity through the

early days of August. On 2 August, Goering issued the final orders for

“Adlertag” which was to commence on 10 August. The last major German

attack before “Adlertag”, which was to be forewarning of the immense

aerial battles yet to come, occurred on 8 August when convoy “Peewit”

was attacked in an immense aerial battle by over 150 German aircraft.

Approximately 30 RAF fighters in an intense dogfight opposed these.

Casualties were high on both sides, the RAF losing 19 aircraft and the

Luftwaffe losing 31 aircraft, along with a significant amount of

shipping lost.

PHASE 2:

“Adlerangriffe” - Destruction of the RAF

Poor weather on 10 August forced the postponement

of “Adlertag” for 24 hours, and was later rescheduled by Goering to 13

August. There was no significant activity on the 10th, but

aerial activity was high on the 11th. A bombing raid on Dover

started the day, followed by three Luftwaffe fighter sweeps but the RAF

generally did not pursue combat. Later in the day, a large German force

of over 160 aircraft assembled for an attack on Portland that was

engaged by approximately 70 British fighters. Heavy fighting ensued and

many aircraft were lost on both sides; 27 by the RAF, and 36 Luftwaffe.

In addition, convoy attacks were attempted in the Thames Estuary and the

English Channel, but worsening weather stopped further action by the

RAF.

Heavy activity was again observed on 12 August,

with the morning started off by the now customary German fighter sweep,

followed by a surprising attack on the British coastal radar chain. Some

minor convoy attacks were also observed, but around noon, a German

aerial force of over 200 aircraft was detected and approximately 58 RAF

fighters were scrambled to oppose it. The German formation split into

two groups; one attacking Portsmouth and the other attacking the radar

station at Ventnor that was seriously damaged in the attack. Aerial

casualties were high on both sides. In the afternoon, an attack of the

RAF fighter bases at Manston, Lympne, and Hawkinge was accomplished; the

first time British mainland fighter airfields had been attacked by the

Luftwaffe. Casualties were high on this day, with 22 RAF aircraft lost

and 31 Luftwaffe.

Poor weather and confusion reigned supreme on

“Adlertag” morning on 13 August. Due to the deteriorating weather, the

attack was postponed until later in the day but the word did not reach

many German units who launched their attacks. Attacks were attempted on

the naval base at Sheerness, and airfields at Eastchurch, Odiham, and

Farnborough, but success on both sides was poor due to the weather. Such

was not the case in the afternoon when the weather cleared.

The largest German aerial armada to date of over

300 aircraft was assembled in the afternoon to attack the docks at

Southampton, the naval base at Portland, airfields at Andover, Detling,

and Middle Wallop, and factories at Rochester. The RAF intercepted these

attacks and heavy fighting ensued. Surprisingly the RAF suffered only 13

aircraft lost to the Luftwaffe’s 34. More importantly for the RAF, only

three pilots were killed with two wounded, leaving many pilots to

continue the battle. After darkness fell, the night attacks continued

with German bombers striking throughout the mainland, even ranging as

far as Belfast.

Fortunately, poor weather limited operations on the

14th, giving both sides a break from the intense fighting of

the previous days. However, attacks were mounted by the Luftwaffe with a

loss of 19 aircraft.

The weather on the morning of 15 August was poor

and forced the cancellation of many planned missions. However, a rapid

improvement in the weather later in the morning allowed the planned

operations to commence into what became the bloodiest day in Luftwaffe

history and a turning point in the BoB. JU87’s attacking Hawkinge and

Lympne accomplished the first attacks of the day, and the radar stations

at Dover, Rye, and Foreness with heavy damage. British Spitfires rose to

defend but were simply overwhelmed by the more numerous BF109 escorts.

Shortly after noon, a large bomber raid featuring the first major attack

of HE111 bombers from Norway struck the Newcastle area followed by JU88

bombers from Denmark. Little damage was done in the raid, but the

bombers were intercepted by British fighters well out to sea and heavy

German losses occurred. The Norwegian based bombers never again

attempted Mass daylight raids.

The afternoon of the 15th saw action

return to southern England when the Germans launched a fighter-bomber

raid on Martlesham Heath airfield followed by a JU88 raid on Rochester

and Eastchurch. Both raids were heavily escorted by BF109’s and the

British fighters rose in strength to oppose the attack and fighting was

heavy. Slightly further to the west, a large strike force of JU88

bombers escorted by BF110’s attacked airfields at Middle Wallop, Odiham,

and Worthy Down. Again, these formations were intercepted by the British

with heavy aerial fighting. Still further to the west, a large bomber

force comprised of JU87 dive-bombers and escorted by large numbers of

BF109 and BF110 fighters struck the Portland area. Here, the British

fighters were particularly effective against the Stuka’s and they

suffered tremendous losses. Later in the afternoon fighting continued

when the Luftwaffe fighter-bombers and JU88 bombers hit Croyden and West

Malling airfields. The heaviest fighting in the BoB occurred on 15

August with the Luftwaffe losing an astounding 75 aircraft in 2,199

sorties and the day became known as “Bloody Thursday”. The RAF also

suffered heavily losing 30 aircraft in 974 sorties.

Combat continued on 16 August, although at a much

reduced level after the all out attacks on the 15th.

Airfields were the primary targets of the Luftwaffe with West Maling,

Tangmere, Westhampnet, Manston, Farnborough, Harwell, Brize Norton,

Gosport, and Lee-on-Solent all being hit. In addition, the radar station

at Ventnor was also successfully attacked. Losses this day were also

heavy, with the RAF losing 22 aircraft and the Luftwaffe 45 aircraft.

After a much needed day off from combat on the 17th,

intense activity resumed on 18 August. Action started around noon, when

heavy attacks were underway on the sector stations at Kenley and Biggin

Hill. The airfields at Croyden and Manston were also hit. Along the

coast, a large attack led by JU87 bombers hit the airfields at Thorney

Island, Gosport, and Ford. In addition, the radar station at Poling was

also hit. The Luftwaffe took large casualties on the day, primarily the

JU87 and BF110, which lost 18 and 17 aircraft respectively. This forced

the removal of the JU87 from the battle, and BF110 operations were

severely restricted. A total of 31 RAF aircraft and 53 Luftwaffe

aircraft were lost in the day.

A combination of poor weather and a needed respite

from operations led to low levels of combat until 24 August. The

Luftwaffe hit airfields at Manston, Hornchurch, and North Weald, but the

most significant activity of the day was when bombs intended for Thames

Haven and Rochester were dropped over central London. This accident

would have a far-reaching effect on the battle yet to come. A total of

22 RAF and 38 Luftwaffe aircraft were lost on the day.

Combat activity continued on the 25th,

however the events of the day were overshadowed by the RAF Bomber

Command attack on Berlin at night in retaliation for the bombing of

London the previous day. While not planned as such, this attack was to

have a profound effect on the remaining battle in which the Luftwaffe

changed their attack strategy from decimating the RAF to attacks on

London. At this time the Luftwaffe was very close to defeating the RAF

and the respite from the almost continual attacks on RAF airfields was

much needed.

Combat activity remained relatively high through

the remainder of August, with the RAF losing 132 aircraft and the

Luftwaffe losing 168 aircraft in the final week.

The first week in September saw continued Luftwaffe

attacks on the RAF bases and also a new emphasis on the aircraft

manufacturing facilities. The attacks were not as massive as those in

mid-August, but casualties remained significant for both sides with the

RAF losing 120 and the Luftwaffe losing 143 aircraft for the first six

days of the month. However, the battle was going to change significantly

on 7 September.

PHASE 3:

“Blitzkrieg on London”

7 September dawned fairly quiet, a few

reconnaissance patrols but no significant air activity. However that was

all to change by the late afternoon when the Luftwaffe launched an

assault force of about 350 bombers escorted by about 600 fighters.

British fighters were scrambled to intercept, but expecting continued

attacks on the RAF airfields they left London largely unguarded. By the

time the RAF had realized that the target was indeed London and vectored

their fighters towards the bombers, most of the German bombing runs were

over. The result was horrific; London was in flames. Four hours later

during the night, the Luftwaffe assembled another attack striking

London. Guided by the roaring fires, the German bombers once again found

London as the target. No respite would be given for the next seven days,

London would be bombed heavily each night.

15 September, which would go down later in history

as “Battle of Britain Day”, saw the daylight attacks on London resume.

However, Fighter Command had the respite it needed from the relentless

attacks on its facilities to rebuild and redeploy to prepare for this

attack on London. When the Luftwaffe launched their major attack on

London around 11:00 AM, the British fighters were ready and met the

German assault head-on. Massive dogfights ensued, and by the time the

bomber force reached London, the bombers were largely devoid of their

fighter escorts. The German bombers then received their first

introduction to the “Big Wing”, five squadrons of British fighters led

by the famous Douglas Bader. Together with other British units, the “Big

Wing” feasted on the bombers causing them to jettison their bombs

haphazardly spoiling their bombing runs. Shortly after noon, the German

bomber force was retreating back to France and hunted relentlessly by

the British fighters. Two hours later the Luftwaffe tried another

attack, but it too was met by massive British force and largely

repelled. In terms of aircraft losses, the battle did not seem all that

spectacular compared to the mid-August attacks, with the British losing

27 and the Luftwaffe losing 56 aircraft, but the tide had turned in the

BoB. For the first time in the battle, the British had the advantage in

strategic position in the air and were not significantly outnumbered.

The Luftwaffe, on the other hand were severely disenchanted believing

they had the British “on the ropes” only to see massive resistance.

On September 19, even though the British did not

know it at the time, the BoB was won when the Germans cancelled

Operation Sealion, the planned invasion of Britain. Although London was

bombed relentlessly at night, only two days remaining in September

featured large scale day fighting, on the 27th and 30th,

although these raids were nowhere near the size featured earlier in the

month.

PHASE 4: Day Attacks Cease

While night attacks would continue on London, and

other important British industrial centers, October would feature an end

to the massive day light raids seen earlier. However, a new German

tactic of bombing raids by Bf 109 “Jabos” was started which were very

difficult to defend against. The Jabo raids were more of a

nuisance than an actual threat, and the BoB was all but over.

Tamiya's

1/48 Scale Spitfire Mk.I

|

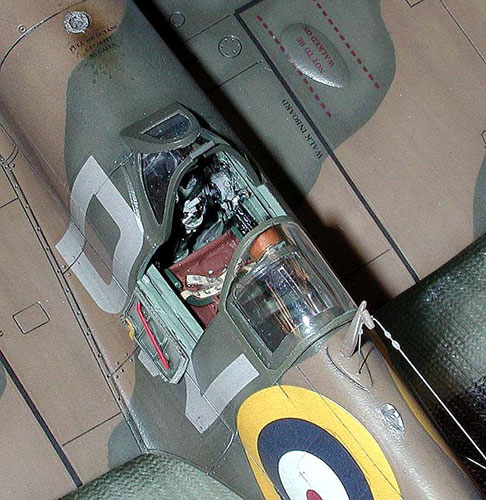

The kit is the Tamiya 1:48 Spitfire Mk I (KIT #:

61032), and nothing more needs to be said as this is an absolutely

fantastic kit! I will freely admit that I am a “resin-o-holic” and

cannot resist any resin set specifically designed for the kit I’m

building. While the box stock cockpit is quite nice (and more than

adequate if you keep the canopy closed!), the Cutting Edge (CE) Spitfire

Mk.I cockpit is absolutely beautiful.

The only fault I have with it is since it is

designed as a “drop-in” replacement (and it does truly “drop-in”) it

snaps onto existing detail in the cockpit, but leaves a rather thick

side area that can be seen if you open the pilot access door (like I

did!).

There is absolutely nothing to report here as the

Tamiya kit builds with only a few minor problems.

The CE cockpit presents no real challenges outside

the usual resin issues (removing pour stubs, cleaning up parts, etc.).

The two areas I had problems with on the kit are the fuselage spine/aft

clear cockpit join and the rear fuselage/wing join that both feature a

significant step that needs to be filled and sanded smooth.

That’s it. Otherwise it’s smooth sailing!

Painting,

Weathering and Markings

|

I chose to model the aircraft flown by the British

610 Squadron. The aircraft is in the early British day fighter scheme of

Dark Green over Dark Earth with Sky undersides.

I

used Polly Scale acrylic paint throughout. After letting the paint dry

overnight, I airbrushed a light coat of Future to prepare the surface

for decaling. The decals went on quite well and responded to Microsol

without any permanent wrinkling. Some silvering was noted in the

extensive clear areas surrounding the squadron codes. After drying

overnight, I wiped the decals off with a moist cloth with Pollys Plastic

Prep to remove any residue and after drying I shot a light coat of

Future over the decals to seal them. I

used Polly Scale acrylic paint throughout. After letting the paint dry

overnight, I airbrushed a light coat of Future to prepare the surface

for decaling. The decals went on quite well and responded to Microsol

without any permanent wrinkling. Some silvering was noted in the

extensive clear areas surrounding the squadron codes. After drying

overnight, I wiped the decals off with a moist cloth with Pollys Plastic

Prep to remove any residue and after drying I shot a light coat of

Future over the decals to seal them.

Next, a light coat of Polly S Flat Finish was shot

to provide a surface for pastels. I used a watercolor based wash of

sepia to highlight the engraved detail such as the panel lines. I then

used pastels applied with a soft brush to simulate the dirt staining

that is commonly seen on these aircraft that were operated from grass

fields. Lastly, I sealed everything with a light coat of Polly S Flat

Finish.

Tamiya models are my absolute favorite to build, as

they usually have no major problems to contend with. This kit was no

exception, and with the only two problem areas noted you can almost

build this kit with your eyes closed! This kit makes a beginner modeler

look like an expert and is highly recommended.

-

Squadron/Signal

Publications, Spitfire in Action #39

-

Smithmark Publishers,

The Battle of Britain

Click on the thumbnails

below to view larger images:

Model, Images and Text Copyright ©

2003 by Bob Laskodi

Page Created 19 September, 2003

Last Updated

17 March, 2004

Back to

HyperScale Main Page |

Home |

What's New |

Features |

Gallery |

Reviews |

Reference |

Forum |

Search