I think this kit has its origins

in old Hawk's offering from the 1950's. The kit basically

comprises two fuselage halves, a single solid main wing and

a few more bits. Sometimes it was hard to distinguish the smaller

parts from the sprue itself.

Interestingly, the model

features only recessed panel lines. But in this case they should

be raised, particularly the ribs embossment over the wings. Even

worse, all decal placement positions are also recessed (remember

these?)! Anyway, I was interested in a simple display model and

decided not to wait the new Pegasus Spirit of St. Louis in 1/32nd

scale. Besides, the 1/8 J-5 engine will probably shadow much of

the little Ryan.

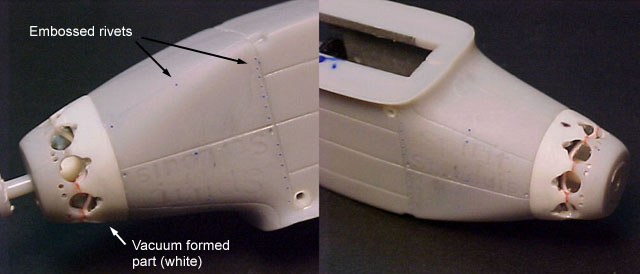

The kit's nose is very bad, mostly because of the crudely

molded cylinder heads.

I vaccum formed a new nose section and drilled the nine holes

for the J-5 engine cylinders (to know how to built your own

vacuum forming table, check my article at Large Scale Planes

website). The holes for the pushrods were also drilled, and this

job deserves careful measurement. As for the cylinders, I made

resin copies from an Aires P&W R2800 engine... not exactly like

the J-5 cylinder heads, but they do the trick. After finishing

the model, I discovered a Russian company called Silniki which

produces a resin Wright Whirlwind J-5 in 1/72 scale. Too late,

again.

At this point the fuselage was virtually done. The recessed

locations for decal placement on the cowling and rudder were

filled with super glue and sanded smooth. I then installed the

lateral windows and embossed some prominent rivets on the nose

panels.

Click the thumbnails below to view larger images:

Finishing the Basic Airframe

|

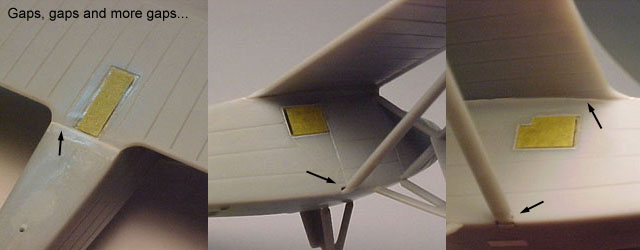

Next, the wing was attached to the fuselage, along with its

supporting struts. The three windows were polished, brush coated

with Future, and masked with Tamiya tape to avoid bluring during

the further handling.

Many spots required filling, but a thick coat of Mr. Surfacer

was enough to handle most of them.

Click the thumbnails below to view larger images:

Small sections of styrene rod were glued along the control

surfaces recesses to simulate the hinges. I then applied a very

light coat of Mr. Resin Primer around the nose and tail areas to

look for blemishes. These were the more heavily worked areas,

and I didn't want to leave a rough surface for the metallic

finish that would follow. In any case, the entire airframe was

polished with a piece of soft cloth, including the primed areas.

Next, a number of smaller details took my attention. I was

particularly disappointed with the propeller and the wheels. The

former had a spinner molded integrally with the blades, and was

devoid of any surface details. The same applies to the wheels,

with some visible details missing. They laked the teardrop

shaped covers of the landing gear axle, and the stitches which

secured the canvas cover of the spoked wheels are not

represented as well.

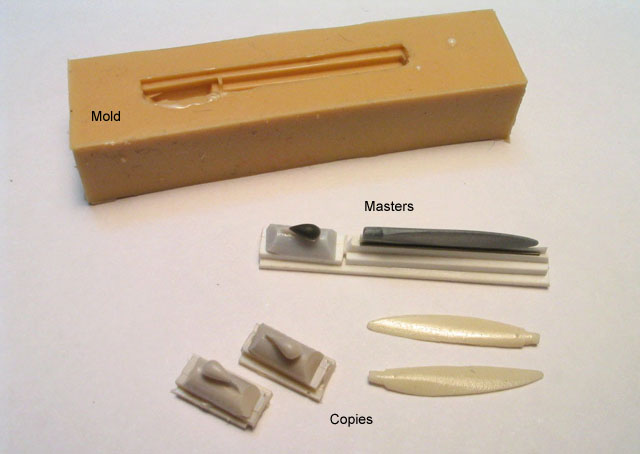

The propeller started its life as an old 1/72 Revell Ki-61

propeller from my spares box. The blades were carefully removed

and the shape of a new spinner was progressively sanded with the

aid of a motor tool, always checking the current profile against

photos. The most difficult part was to scribe the panel lines

around such a double curvature, small part. Several rivet lines

were added to the spinner. Once again, I found too late that

this type of spinner was not used during Lindebergs's famous

flight (in addition, at least three types of spinner were used

in the Ryan NYP - one of them with a very round tip). I then

reshaped the blades and opted to make molds of everything, just

in case. A master for the wheel tear drop covers was made from a

chunk of plastic.

To simulate the stitches around the wheels canvas cap, I

simply took a fresh #11 blade and pressed its tip against the

edge of the kit parts. This is done by free hand, trying to keep

the spacing as even as possible. Then it was just a matter of

crossing my fingers to the effect show up with a careful dark

wash after painting.

Next, I had to work on the engine cylinders... all nine of

them plus a couple of spares. Basically, I added styrene rods

bent to proper shape in pre-drilled holes to simulate the

exhaust pipes. The same method was used for the intake ducting,

but soldering wire was used instead of styrene.

Another bit added was a pair of handles on each side of the

bottom fuselage, just ahead of the stabilizers. These details

are clearly visible in vintage photos, and were used to handle

the aircraft. I made them from fine brass wire and installed

with white glued in pre-drilled holes.

While the resin copies were curing, I cut 18 little pushrods

from stretched sprue. It is imporant to check the rod diameter

to assure visual consistency and that they will fit the holes

drilled around the cowling.

Click the thumbnails below to view larger images:

Since the kit has no representation of the carburator, a new

one was scratchbuilt from pieces of plastic using the William

Bothers J-5 kit as a reference. A couple of hoses coming from

cylinders 5 and 6 provided hot air to the carburator. They were

made from bulb filament coil with cooper wire inserted inside.

The wire makes the coil remain with the proper shape after

bending.

I used Model Master Aluminum Plate buffing metalizer to paint

this model. I mean, ex-buffing. I know many modelers don't like

this product due to its bad adherence. Here is the trick (it

works with all others MM buffable metalizers, too): take a new

bottle of metalizer and leave it open overnight. Because its

solvent is highly volatile, what you will find in the next

morning is a disk of pure metalizer pigment on the bottom of the

bottle. Don't cry... fill the bottle up with 2/3 Model Master

sealer and 1/3 Model Master metalizer thinner. Shake, shake,

shake... The result is an almost-non-buffable metalizer paint

with the same adhesion properties of the MM metalizer sealer.

Now it can be masked like any enamel paint. Same pigment, same

coverage, we just exchanged the paint carrier fluid. On the

other side, it is now much harder to be polished, but during the

experiences I achieved different paneling effects by polishing

the surfaces with SnJ powder or fine glitter.

The resulting finish is a bit different than the original

metalizer, too. In the case of MM Aluminum Plate the recipe

gives a slightly darker aluminum color, but to my eye this is a

perfect match for aluminum doped surfaces... exactly what I was

looking for.

Click the thumbnails below to view larger images:

I think the most difficult thing during the painting was to

make the paint hit the upper sides of the main wing struts

without flooding adjacent areas. Using a Badger 100 with fine

tip in one hand and a piece of paper to be used as a barrier in

the other, I spend half an hour applying the aluminum finish to

the whole model. Half of this time was spent trying to cover the

upper surfaces of the wing struts.

The only non aluminum areas were the engine bits and the

tires. The cylinders and pushrods were painted with Floquil

Engine Black, which is dead flat. Later I brushed the rock

covers and the pushrods with straight Future to make these areas

gloss, producing a distinctive contrast with the finned region.

This effect is very characteristic in vintage radial engines.

The wheel tires were painted with the late Aeromaster Tire Black

enamel. The canvas cover was painted afterwards with the aid of

a drafting template.

Simulating the "Brushed Panels"

|

The most challenging step of this project was to replicate

the 'brushed' panels around the nose. The Ryan NYP was in fact a

modification of another Ryan aircraft, where every available

space was used to store fuel, including the nose area. To add

the necessary strength and avoid direct sun light, the

windscreen was removed while the whole nose was paneled. Since

this was a one of a kind aircraft, no steel tool was produced to

forge these curved panels. Instead, they were manufactured by

hand. I still don't know whether the panels were brushed to

force the plates to conform the (wood) patterns or it was just

an aesthetic measure.

It is worth to note that the original Spirit of St. Louis on

display at the Smithsonian Museum currently shows a distinctive

gold hue on these panels. Judging from vintage photos, it was

not this way back in the 20's. This is probably a result of

progressive oxidation of the steel panels. I mention this here

because I found some models of the Spirit of St. Louis with

their nose painted with gold tints. I think this is incorrect

unless you are building an exact replica of the aircraft as

displayed today.

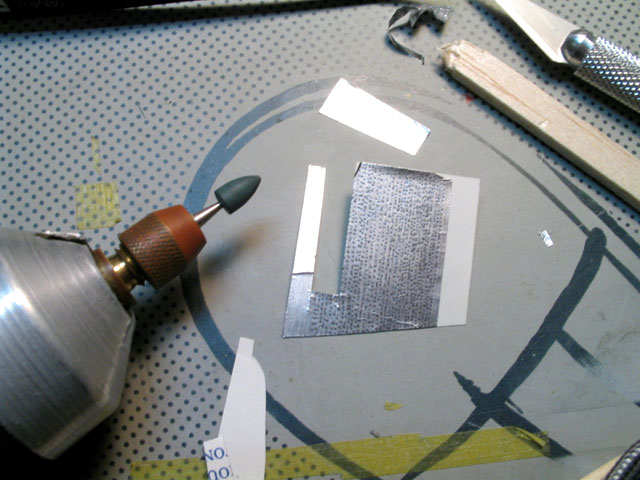

Well, I tried various techniques to replicate the effect on

scrap parts. Too many to list here. After posting for help in

Hyperscale forum, some fellows came to rescue advising me to do

exactly as it was done in the actual machine: to brush the

metal. And so I did. The method uses Bare Metal Foil (I used

matte aluminum) brushed with a motor tool. I took a good piece

of Bare Metal Foil and blured small dots all over the area. The

secret is to use an adequate tool to burnish the dots on the

foil before its application. After a few trial and error

attempts, I elected a small conical rubber-type polishing tool

resting for years on the bottom of my accessory case. Sorry, but

all I know about the stuff is I bought it in a dentistry shop

retail, and it is intended for polishing dental prothesis. I

installed it in a slow speed motor tool and painfully burnished

endless rows of marks. Very boring, but all it takes is to keep

the tool perpendicular to the foil sheet, light fingers (just

let the abrasive head touch for a second the foil, then move on

to the next one - never put pressure on it), and patience. I

almost went blind doing this, but thankfully this is a 1/72

model. Given my lack of talent with Bare Metal Foil, I ruined

some sheets during the application and had to go back and make a

few more. The sheets were applied by panel using the standard

method: cut oversized, trim the excess (use the panel lines as a

guide) and move to the next panel. The only deviation was the

top panel of the cowling, which has a double curvature area

around the wing leading edge. In that case I applied two stripes

of foil to make the job easier, then retouched the brushed marks

with the motor tool along the joint line. You can't tell where

the joint is...

After foiling the whole nose, I burnished the scribed panel

lines with a piece of dampened balsa wood. A light wash of

black/brown was applied before the installation of the cylinders

to highlight the panel lines and rivets. Once I was satisfied,

the cylinders were individually pressed into their holes with

white glue. Tragedy almost struck when I realized the during the

pushing some panels slid a bit from their location. I carefully

removed the cylinders, slid back the offending panels and

started over, this time tearing off as much as possible of the

foil from the holes. Alignment is critical here. I'm still

unsatisfied with the position of some cylinders...

The decals were all applied before the installation of the

smaller details. I was very concerned about how invisible

would be the kit's Invisa-Clear decal film on the rudder,

since I planned no top clear coat. In addition, the brushed

marks on the cowling could be a potential source of silvering.

In the end the result was very good, with no silvering

at all. I don't know what is your experience with Invisa-Clear

decals, but I guess that my old indian recipe for the

metalizer helped to avoid problems. On de other hand, I found

all fuselage decals a bit oversized to fit properly between

the panel lines.

The carburettor was then installed. I had to reinstall a

couple of misaligned cylinders. Then the tail skid, the wheels

and their tear-drop axle covers were glued in place.

Next, all pushrods were individually glued in place using

white glue. At this point I test fitted the propeller and

retouched some of the engine areas with Future, as

mentioned above. As a final touch, rust colored pastel

chalk was lightly rubbed around the end of each exhaust

pipe. The N-X-211 code letters were applied on the top and

bottom of the wing. At the beginning of this project, I

decided not to fill the decal placement recesses for the

wing decals to avoid rescribing the ribs. I still regret

the decision, as the recesses are very visible. To avoid

further problems I trimmed off any clear film from the

wing decals, only to discover that they don't match

perfectly the corresponding recesses. Still passable,

though. The spinner received a black wash to highlight the

rivets and other scribed details. The propeller blades

received logos stolen from another kit. Almost there...

Click the thumbnails below to view larger images:

The frames of the cockpit's ceiling window are thin

stripes of Bare Metal Foil carefully pressed in place. The

three fuel tank vents on the top of the wing are L-shaped

stretched sprue installed in tiny pre-drilled holes. I

photoetched a set of very small blades for the wind driven

generator, glued them at the end of a styrene rod,

painted, and installed it on the fuselage spine. The last

detail added was a stretched sprue pitot tube. The

weathering was limited to a light wash on the wheel

covers, cowling and spinner.

And that's it. The engine/nose area resulted in a lot

of work, but careful planning saved me a lot of trouble.

In retrospect, I should fill the decal markings on the

wing. Apart from that, I'm very satisfied with the result

considering the kit used. I can't wait to see it displayed

side by side with the J-5 engine. It was an enjoyable

deviation from guns, bombs, and swastikas... but at least

I now have a decent model of a historically very

significant aircraft.

... and of course, my thanks to many HyperScalers and

HotWashers for the help.

Home |

What's New |

Features |

Gallery |

Reviews |

Reference |

Forum |

Search