|

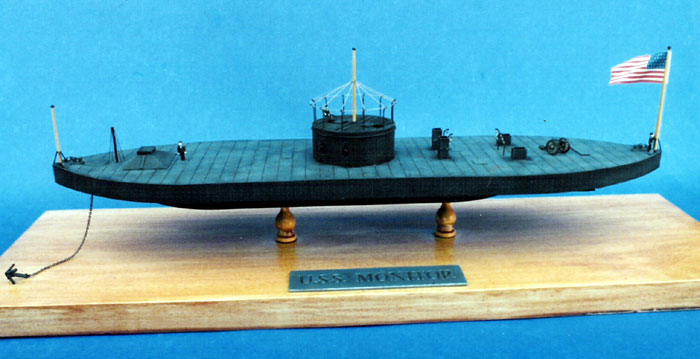

“Cheesebox on a

Raft”

Union Ironclad USS Monitor

by Charles Landrum

|

|

|

Union Ironclad USS

Monitor |

Battle Axe's

1/144 scale Ironclad USS Monitor is available online from Squadron.com

In the United States, the epic struggle of the

American Civil War continues to fascinate and even invoke visceral

reactions 140 years after its conclusion. While the other naval actions of

the war have faded with time, the “duel between the ironclads” USS

Monitor and CSS Virginia is ingrained in the historical

conscience of the nation. (It is often more commonly known as the “Monitor

and the Merrimac”, because Virginia was rebuilt from the

scuttled steam frigate USS Merrimac).

The Monitor was a technological marvel in a

time when navies still relied on sail and broadside guns. Her designer,

John Ericsson an eccentric genius of Swedish birth, was both hailed and

derided by the Navy and the public. To many the radical USS Monitor

was going to be the savior that would turn the tide of misfortune suffered

by the Federal Government to that point. She came into being to defeat the

monster ironclad the Confederacy was building to lift the Union naval

blockade of it’s waters; it was to be a contest of David versus Goliath.

Despite this popular acclaim, Monitor was derisively referred to as

a “cheese box on a raft” by many skeptics.

So the historical stage was set when Virginia

sailed out on March 9th to finish the ravaging of the Federal

fleet that she began the day before. USS Congress was still burning

and only the masts of the USS Cumberland remained above water,

when Virginia came out for round two. In the morning light, the

crew of Virginia saw a low form silhouetted in front of USS

Minnesota, their next intended victim. They soon realized that the

vessel that looked like a water tender was in fact the much-rumored Union

ironclad. The ensuing engagement consumed the daylight hours with neither

opponent really gaining the upper hand. Monitor was less armed but

more maneuverable, while heavily armed Virginia sluggishly sought

advantage. It was a tactical draw.

Virginia sailed back up the Elizabeth River to

Portsmouth never to threaten the blockade again, leaving the Hampton

Roadstead in Union hands and the James River the only

Confederate-contested waterway in Virginia. It was on this river that

Monitor spent her remaining operational months, protecting the flanks

of General McClellan’s ill-executed campaign to Richmond. Monitor

was lost later that year on December 31st, 1862 to a fierce

storm off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. She had been in tow to

Charleston, South Carolina for the impending naval siege of the birthplace

of the rebellion.

Last year, the US Navy and the National Oceanic and

Atmospheric Organization raised the turret of USS Monitor 140 years

after her loss, culminating a 25-year recovery effort. The numerous

artifacts recovered from Monitor are being conserved at their

permanent home in the Mariners Museum in Newport News, Virginia. It is

perhaps no coincidence that Battle-Axe chose this time to release a new

kit of this important ship.

References:

-

Miller, LT Edward M.,

U.S.S. Monitor: the Ship that Launched a Modern Navy. Leeward

Publications Inc., Annapolis, MD. 1978.

-

Tucker, Spencer, Arming

the Fleet: U.S. Navy Ordnance in the Muzzle Loading Era. Naval

Institute Press, Annapolis, MD. 1989.

-

Besse, Summer B., C.S.

Ironclad Virginia and U.S. Ironclad Monitor, Mariners Museum, Newport

News. 1937 (reprint, 1978).

Battle Axe's

1/144 Scale USS Monitor

|

Out of the box, the 1/144 scale Battle Axe kit of

USS Monitor depicts Monitor’s stripped-down-to-fighting-trim

configuration at the time of her duel with Virginia. For the

engagement Monitor was ballasted low in the water, her intake and

exhausts stacks removed and stowed, as were her staffs and davits. She was

configured as Ericsson intended, offering the smallest possible target.

However, this makes for a rather plain ship model.

My build-up of the Battle Axe kit depicts Monitor

as she was outfitted for James River duty, June 1862. I chose this

configuration because it typifies the blockade duties the Monitor

and subsequent classes of monitors were primarily engaged in, and offers

more visual interest.

This configuration required the following additions

to the kit:

-

Sloped armor around the

pilothouse; added after the battle with Virginia to reduce the

proven vulnerability of this critical station.

-

Intake and exhaust stacks

-

Flag staff, jack staff,

turret staff and signal pole

-

Davits

-

Awning stanchions and

rigging on the turret

I chose to leave off the deck-edge stanchions and

lifeline and the turret lifeline, for these were seldom rigged on blockade

duty. I also left off the awning for better viewing inside the turret.

The kit is a fairly accurate representation of the

ship and is not hard to build despite initial appearances. The model

compares favorably to available drawings and references and captures a lot

of subtle detail overlooked in other kits. The accuracy of the turret is

the principal weakness of the kit. The one sheet instructions were for the

most part clear and provided scale drawings in scrap views of the more

complex assemblies. The slightly rough surface molding of the low

injection molding process is an advantage in replicating the cast iron

plate of the ship. The kit comes with an accurate 34 star flag and a small

photo-etch fret, which includes the ladder for the turret exterior and an

anchor chain. The nameplate is nicely molded in styrene.

The breakdown of the parts works well. The deck is

molded as once piece, as is the hull, so there are no large seams to deal

with. With that said, the kit does suffer from heavy sprue attachments and

large injector pins. Fortunately the injector pin marks/residue are not

visible but they do interfere with the fitting of components.

The Hull

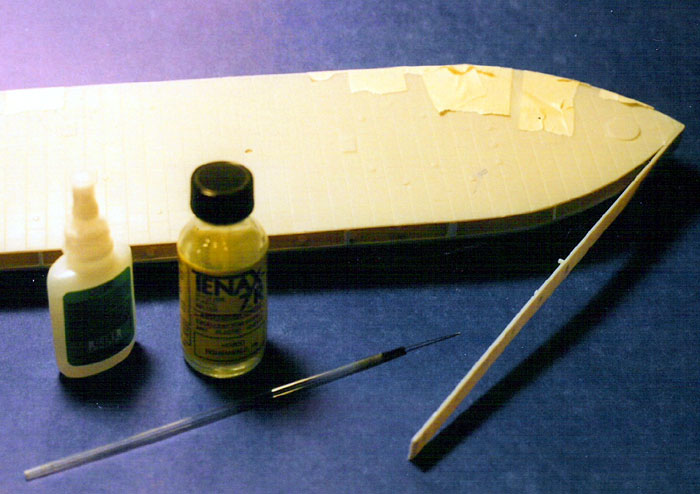

I started the kit with the “raft”, adding the wells

that get sandwiched between the hull and the deck. Battle Axe got the

shape of the propeller well right based on my interpretation of the

available drawings; it fit with minor sanding. In assembling the two

halves of the anchor well, I found that it was slightly oblong in shape,

so I replaced it with a styrene cylinder from my spares box. I drilled a

.06 hawse pipe, 3/32” down from the top of the well and added a fairlead

shaft of .047 styrene rod across the diameter of the well at the same

level as the hawse pipe.

Next I fitted the supports for the deck, which

required considerable action with my sprue cutter to remove the forest of

injector pins. Only two supports “beams” are provided to set the spacing

between the deck and lower hull. While this may be adequate, I erred on

the side of caution and added additional supports fashioned out of .04

styrene. There was no easy way to make the alignment between the hull and

the deck, so I eyeballed it in with a steel rule as a straight edge,

checking alignment at various points along the edge!

The anchor well lines up with its cover plate, but

the rectangular access cover to the propeller well does not. The location

of the access plate is too far aft based on the drawings, so I shaved the

old one off and fashioned a replacement from .02-inch styrene and

relocated it slightly forward. Once the raft assembly was dry, I turned it

up on end and sanded all edges even with 150-grit sandpaper taped to my

bench top. This had the added benefit of chamfering the ends of the

supports beams to match the curvature the hull.

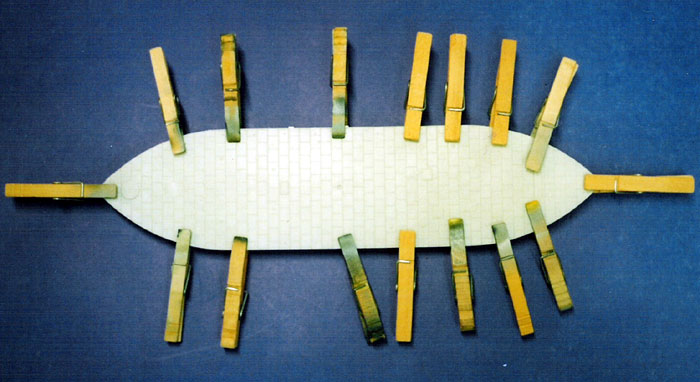

Adding the side plate was easier than I believed it

would be. The side armor comes in four strips, two per side, with a

designed overlap. I eliminate this overlap piece when I discovered that it

was not sufficiently deep to accommodate the thickness of the overlapping

section. Instead I sanded it for a tight butt joint. The side plate does

need to be chamfered at the end to achieve a point at the bow and stern

joints. I used CA to fix the plate at the bow and worked aft attaching it

with liquid cement.

The alignment along the deck edge and hull was good.

I used tape to keep it from springing out. Using liquid cement to make the

butt joint, I proceeded aft with the second piece. I ended up only

trimming of 1/8” of side plate at the stern and then chamfered it as well

for a good joint. I repeated the process on the other side.

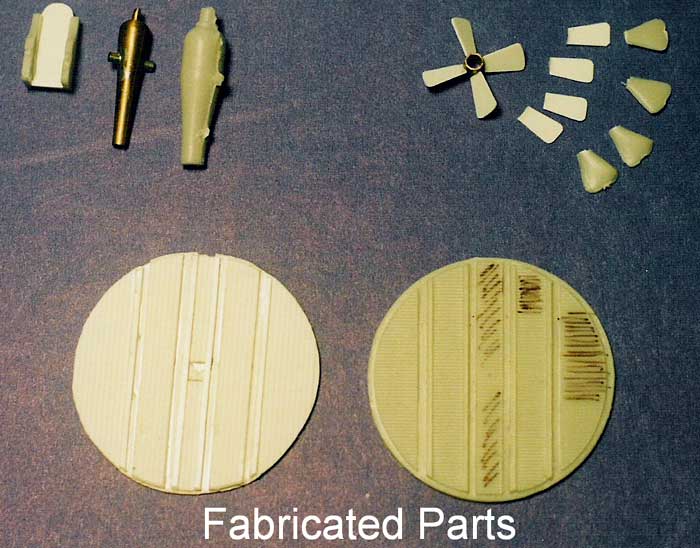

The Monitor’s propeller and rudder, protected by a

skeg, was an ingenious design for a vessel whose intended use was in the

shallow waters of the coastal estuaries of the Eastern seaboard. The kit

captures this design well. However, the individual blades of the propeller

are overly thick. In addition, the propeller hub molded to the end of the

roughly cast shaft is too rough. I opted to make a new, more realistic

propeller from scratch from styrene. The blades on Monitor’s propeller

were variable pitch - that is each blade has a helical twist from the hub

to the tip. Even though Battle Axe captured this variable pitch in their

overly thick blades, I felt that thinner blades with a fixed pitch would

be more realistic in appearance. If I had made the blades from brass, I

could have varied the pitch, but I opted for the less time-consuming

styrene solution. I made the new propeller hub from .25-inch brass tube

cut to a length of 6/32. The blades were shaped made from .02 X .250

styrene strip. These were then glued to the hub at the proper angle using

CA. I made the propeller shaft from .100-styrene rod.

Assembling the skeg assembly required only clean up

work. I drilled a hole for the shaft and then glued the Y-shaped shaft

support to the hull. Then it was just a matter of sliding the shaft

through the propeller hub and shaft support. I used CA to secure the

propeller and liquid cement to secure the shaft. There was no problem

fitting the rudder, which I left centerlined.

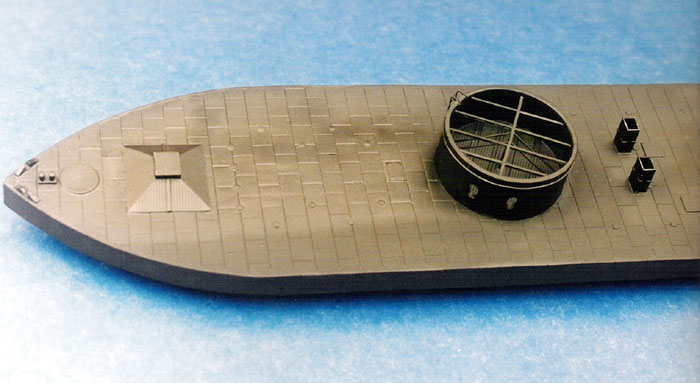

Topside

With the hull together, I concentrated on adding the

deck details. As is typical with most kits these days, the instructions do

not identify the components of the subject. So I wanted to take a moment

to identify the molded features of the deck. Between the stacks are two

hatches, which were the access hatches to the coalbunkers. The raised

round bumps on deck, represent the thick glass prisms that admitted

daylight below decks. The deck edge stanchion sockets are represented by a

series of evenly spaced dimples. These subtle features are why this kit is

the most accurate available.

I used the kit bollards and open chocks, though the

open chocks required a lot of cleanup and were a bit fragile to work. I

assembled the pilothouse per the instructions and then glued it in place

as well. It required a lot of cleanup to get plumb.

As I mentioned earlier, the pilothouse was found to

be too vulnerable in combat and additional armor protection was added.

(This forward location of the pilothouse proved impractical and all

subsequent classes of monitors located the pilothouse on top of the turret

to provide greater protection and ease communications.) I replicated this

armor, made from T-bar, by using .04-inch spacing, .02-inch thick V-groove

siding. I cut four sections using enlarged drawings from the Leeward Press

publication as a template. I chamfered the sides for better fit and

started with the forward piece. I used liquid cement to glue it just below

the view slits. I then fitted and secured the sides and finally fitted and

secured the aft piece. The side armor also received prototypical

reinforcement strips made from styrene strip.

Next came the stacks. On the Monitor, these were

removable and I believe came apart in sections for storage below. The

forward two were the exhaust stacks and the aft two the intakes. For some

reason, Battleaxe chose not to include the stacks, although they provide

the deck-level grills. It was an easy matter to make stacks from

.02-styrene strip. I built them up in place and added small details from

scrap styrene. Adjacent to the stack were four J-bar davits, their

locations being molded into the deck. I made four, .5-inches tall from

brass wire. I attached spare PE blocks and tackles in a stowed position.

Finally the signal pole forward of the pilothouse was made from styrene

rod and the stays rigged with fine brass wire.

The

Turret

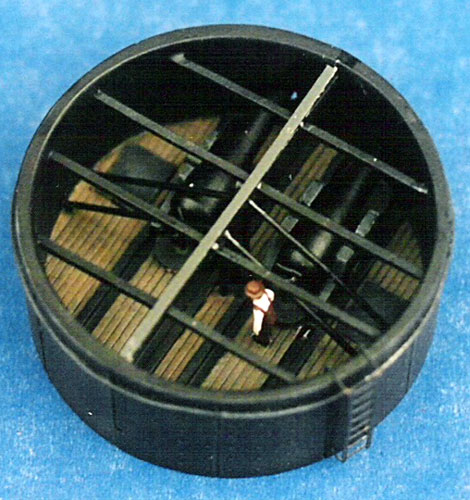

Built straight from the box the turret is a passable

replica. What is provided is a floor plate and roof plate, both with

recessed lines, and side plating with bolt head detail. The turret sides

are molded in three sections, which I initially thought odd. But during

assembly found this breakdown to be a clever way to avoid an oblong

cross-section, which two halves might create. In the course of my research

I found that the turret is a less than a correct representation.

The root problem with the kit’s turret is the fact

that the guns provided are too large. What Battle Axe provides are guns

that scale out to be 15-inch Dahlgren smoothbores found in later classes

of monitors. This is somewhat understandable given the fact that there are

readily available drawings of these later turrets. Monitor, however

carried the largest gun then available, which was an 11-inch smooth bore.

There is quite a difference in size in 1/144 scale. The overly large guns

throw off the dimensions of not only the turret floor, but the gun ports

in the turret as well. The correction is involved and time consuming. I

opted to fix the turret and to detail the interior, although it would be

mostly hidden. Also, as a compromise to the molding process, Battle Axe

provides a solid turret roof with engraved lines to represent the spacing

between the inverted railroad rails that formed this roof. In this scale,

the viewer should be able to see into the turret, so I opted to correct

this flaw as well.

First things first, I needed scale 11-inch Dahlgren

guns. Armed with the book Naval Ordnance in the Muzzle Loading Era,

I found dimensioned period drawings of an 11-inch gun. I looked at

mail-ordering the guns from Blue Jackets, which carries Dahlgren cannons

in their line of ship fittings, but I was unsure if the dimensions would

match. A friend, who is a pattern maker, offered his assistance. With a

copier, I was able to create a reduce-scale drawing from which he turned a

scale barrel from brass. He made a silicon rubber mold and poured

beautiful castings out of white metal.

Armed with properly scaled barrels, I then had a

reference to scale the rest of the work in the turret. I made narrower gun

carriages using the kit provided gun carriage sides a new carriage floor

from fabricated from .02x.250 styrene strip. The carriage then became the

benchmark for the rest of the dimensions in the turret. Using the kit

floor as a circular template and Stevens Institute drawings of the

Monitor found in the Leeward Press book for reference, I scratch built

a new floor from styrene sheet and strip. Leaving space for the track, I

made the floorboards from .04-inch spacing v-groove styrene. Unlike the

kit part, the planking of the turret floor ran parallel to the gun tracks

(If you use the kit provided turret roof this error is hidden and not

worth correcting.) With the floor done, I fitted the sides of the turret.

At this point the instructions are unclear as to which end of the turret

facing is up! The floor should be raised, so the recess partially up the

inside face of turret is for the floor; he recess even with one edge is

for the roof. I filled the gun ports with styrene and CA and re-bored them

with a pin-vise to better align with the new guns and carriages. Of note,

the gun ports on Monitor were formed from three overlapping holes

bored through the armor. In the haste to get the ship to sea, the

scalloped edge was not ground smooth. Try as could, I was unable to

duplicate this appearance!

The

next step was to detail the inside of the turret. With this work done, I

painted the turret interior with a base coat of flat black. I hand painted

the deck with dark tan and when it was dry, gave it a black wash. I also

spray painted the gun carriages and barrels flat black. The carriages were

dry brushed with Euro 1 gray but the barrels were not. The guns were then

carefully inserted into the turret. The

next step was to detail the inside of the turret. With this work done, I

painted the turret interior with a base coat of flat black. I hand painted

the deck with dark tan and when it was dry, gave it a black wash. I also

spray painted the gun carriages and barrels flat black. The carriages were

dry brushed with Euro 1 gray but the barrels were not. The guns were then

carefully inserted into the turret.

I fabricated gun stoppers, a pendulum of iron plate,

as well and rigged them with PE blocks (pulleys) and tackle inside the

front facing of the turret, rigged clear of the gun ports. I made the

turret roof with Plastruct t-bar stock to represent the railroad rail that

was actually used. I set the spacing with the thickness of a steel

machinists rule. I left openings on either side for the sliding hatches,

which I made from .02-inch styrene . To avoid overspray through the slats,

I hand painted the bars.

Click the

thumbnails below to view larger images:

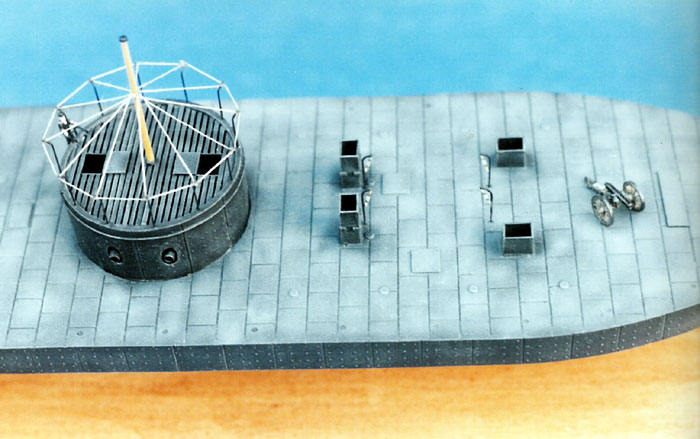

The last task was to add the turret exterior details.

The PE ladder provided in the kit was bent and installed. Fine brass bead

wire was used to make the tie down ring around the circumference of the

turret. Stiffer brass wire was used to make the awning stanchions at the

top of the turret. These were set into predrilled holes.

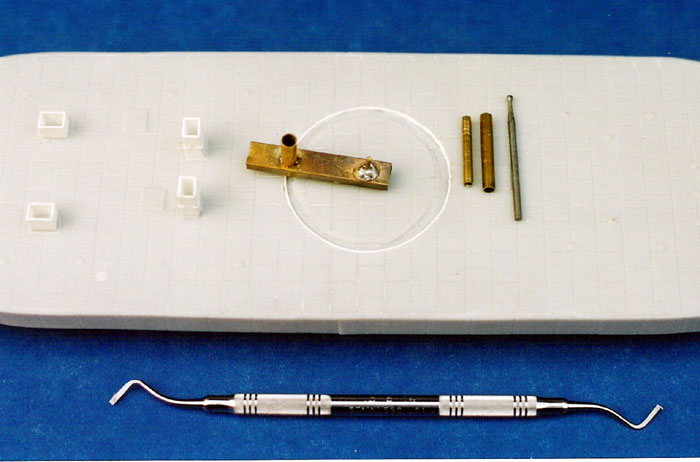

Once I had the basic ship done, there was one detail

that troubled me. The turret in the kit sits on the surface of the deck.

On the Monitor, the turret rested on a recessed brass track. I

wanted that recessed look! So after much angst and with technical

assistance from my pattern maker, I fabricated a jig from brass to allow

me to cut a circular track for the turret. This was not a process for the

faint of heart, but I was committed (or should have been!) The jig was set

up for use with my Dremel motor-tool with a small cutting head. Despite

the softness of the plastic I was able to achieve a reasonable track. I

cleaned up the race with a dental scraper and then ensured a tight fit

with a piece of styrene strip glued along the outer wall. Voila, I had the

look I wanted with only the addition of a few more gray hairs!

Here was an area that demanded a lot of research.

What color was the Monitor? My preconceived notion was black based

on the photos and models I had seen. But there is an undercurrent of

discussion on the web that suggests dark grey. Careful study of available

photos in comparison to the officers and crew on deck led me back to

black. Plus most of the machinery from the period was black. So black it

was. But then that raised the question of the underwater hull. Profiles I

have seen show a red anti-fouling, but I could find no written proof.

Besides If this was indeed the first iron warship, who would of thought of

anti-fouling paint? Plus Monitor was so rushed to get to sea, there was

not the luxury of time, so I opted to keep the ship black from the keel

up. But to give the ship some visual interest I decided to fade the deck

as surely it had been from the Virginia sun.

I painted the model with a base coat of Model Master

Interior Black enamel.

I then used Model Master European 1 Gray to fade the

deck plates. At this point I realized that the deck plate recessed detail

stopped short of the gunwale due to the side armor. I elected to continue

these lines to the edge by scribing with a razor saw. Happy with the

result, I gave the deck plate joint a wash of flat black. To even out the

appearance of the deck plates and the to highlight the small details I dry

brushed the entire model with Euro 1 Gray. In particular this technique

helped emphasize the rivet detail of the hull and turret, the sloped armor

of the pilothouse and the rail spacing on the turret roof. A finish coat

of Testor’s flat lacquer gave the model a uniform, muted look.

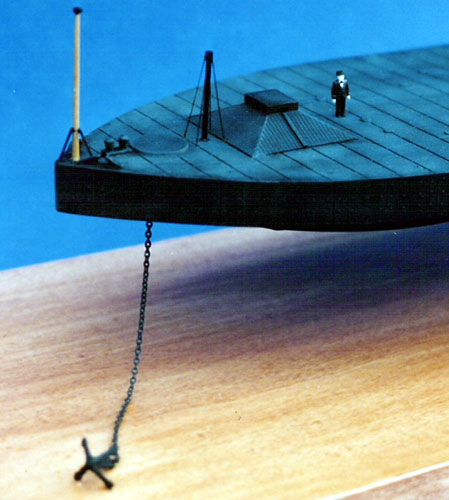

For

the anchor and chain, I used the kit anchor and chain from cosmetic

jewelry, bought in a discount store. It was then dipped in Blacken-it for

a more scale appearance. I carefully threaded and glued it into the hawse

pipe and then connected the anchor with a link made from brass wire. For

the anchor and chain, I used the kit anchor and chain from cosmetic

jewelry, bought in a discount store. It was then dipped in Blacken-it for

a more scale appearance. I carefully threaded and glued it into the hawse

pipe and then connected the anchor with a link made from brass wire.

The deck gun was typical of the period. Ships on the

blockade, especially the monitors, often carried a smoothbore howitzer on

a three-wheeled iron carriage to quickly respond to skirmishers and

snipers. It obviated the need to power up and man the large turret. The

cannon is a 10mm scale Napoleon smoothbore field carriage made by Starfort

Models in the UK. It is exquisitely molded in white metal as are the three

Union artillerymen that come with it. The crew figures are N-scale model

railroad figures by Model Power, repainted in period naval uniforms. I

added them to convey a sense of scale of the sheer bulk of the vessel.

The staffs and poles of Monitor required a

traditional ship modeling approach. Styrene rod, although suitable for the

small signal pole, lacks stiffness worked to create a suitable taper. So I

made the staffs by chucking 1/8inch birch dowel into my Dremel and sanding

a tapered into the dowel. The wood was sealed with a one step light stain

and polyurethane. Once stepped into position, I fabricated supports from

brass wire and rigged the awning with from brown polyester thread.

The base I am not happy with, but it will do until I

make a new one. The wood is birch and did not take the finish evenly,

which may be a more of a function of my wood working skills than the

suitability of the wood! I used the beautifully molded kit nameplate for

the base. It was sprayed with Model Master Anodized metal Metalizer for a

machined look and washed with Model Master flat black acrylic to highlight

the letters. I think it makes an appropriate industrial presentation.

As the last act, I raised the ensign!

I substituted the kit flag with a larger one from

Model Shipways. I tried to shape the flag to give it a more realistic

appearance. Leaving a white “fabric” border, I attached it to the halyards

by folding over the paper and gluing it with white glue. The halyard is

white silk thread.

Overall, this Battle Axe kit was an enjoyable build.

Despite the kit limitations, it is the most accurate model of Monitor

available and has potential for a lot of configuration modifications.

Though not designed as a waterline kit, it would make an interesting

waterline display, perhaps with a longboat rowing out. I recommend it for

anyone interested in this period of naval history. Far from graceful, the

Monitor was rugged, utilitarian and business-like in appearance,

not unlike the early tanks that would come 50 years later. In this regard

Battle Axe captures the ship perfectly.

Thanks to

Squadron for the review sample

Charles Landrum is a defense consultant now retired from the US Navy. A US

Naval Academy Graduate, he spent the bulk of his 20-year naval career at

sea serving on six ships of the Atlantic Fleet including USS SAIPAN, USS

ENTERPRISE, USS BIDDLE, USS HAYLER, USS HARRY E. YARNELL and USS KIDD. He

also accumulated time and experience on the ships of the NATO navies,

especially Canadian. An avid modeler and Hyperscaler, he concentrates his

modeling efforts on the ships and aircraft of the US Navy. He and his

family continue to reside in Norfolk

Click on the thumbnails

below to view larger images:

Model, Images and Text Copyright © 2003

by Charles Landrum

Page Created 22 October, 2003

Last Updated

17 March, 2004

Back to

HyperScale Main Page |

Home |

What's New |

Features |

Gallery |

Reviews |

Reference |

Forum |

Search