|

The 1/72 Scale Contrail

Sutcliffe

North American XB-70

by Bill "C2C" Dye

|

|

|

North American XB-70

|

HyperScale is proudly supported

by Squadron.com

I know what you’re thinking: ‘Why the heck did this guy build this

kit when there’s an injection kit!?’ Well, simple answer: when I built

this monster, the injected kit wasn’t out yet – not for several years.

Over the last 15 to 20 years I’ve built other vacuform kits, e.g. XB-35

Flying Wing, FJ-1 Fury, KA-3D Sky Warrior. It always seemed that within

a few years of me building the vac kit an injection kit would come out.

How many times I would hear at the San Jose or Fremont ,California IPMS

meetings, “Hey Bill, did you hear? . . . someone’s coming out with an

injection kit of the ________” (fill in the blank). It got to the point

that I was getting requests! “Would you build the Rareplanes Aircomet so

I can build it later as an injection kit.” Eshh!

The XB-70, to me, is one of the coolest aircraft ever designed and

flown. To imagine that this huge machine saw around Mach 3 is mind

boggling. I can only imagine a scene like that in the movie, “A

Gathering of Eagles” where all of the B-52s were taking off – except

they're B-70s instead!

This aircraft was once destined as a supersonic replacement of the B-52,

it began a test program in the 60’s with two machines. One had no wing

dihedral and another 5 degrees. With a higher cruise altitude and

supersonic speed the XB-70 was to fly higher than the opposition to its

target(s). Unfortunately missile technology surpassed the XB-70’s

altitude and speed safety area and growing costs led to its demise. The

aircraft seems to be well known by the infamous and fatal crash

involving an F-104 and other aircraft prior to the program cancellation.

I saw the remaining XB-70 at Wright Patterson AFB in 1972 (when it was

outside, I heard that they built the new museum around it!). I had an

“Instamatic” camera and wanted to fill the frame with the airplane and,

of course, my bride (no, I wasn’t on my honeymoon but it was still less

than one year . . . that counts as a bride). I moved farther and farther

away to fill the frame. I moved back and back until I finally got the

entire aircraft in the frame. Later, when I got the photos back from the

drug store, in the photo I saw a pink dot at the base of the nose gear .

. . . my wife wearing a pink blouse. She hates getting her picture taken

so I wasn’t surprised when she said she wished all of my photos of her

would be like that! Critics!

As an aside . . . . .

To digress further: I worked for Rockwell International on the Space

Shuttle from 1973 to 1977. I was a young punk kid working as a wind

tunnel test engineer in the Aerodynamic Heating Wind Tunnel Operations

Group of the Flight Sciences Department in Downey, Calif. I was in model

heaven! I worked on the aerodynamic heating models for ascent and entry

heating. (Oh yea . . . . we weren’t allowed to say re-entry because it

hadn’t left the earth for the first time!. . . . sounds like a ‘Dilbert’

to me.) I was a wind tunnel test engineer and I was responsible for

getting the models designed, built and conduct the tests to collect the

data that the smart (4.0 students) would analyze.

I got to test many

different types and sizes of models in several NASA and Air Force wind

tunnels. I did most of my testing with an OTS model (Orbiter + Tank +

Solid rockets) with the Orbiter about 24 to 30 inches nose to body flap.

I don’t remember the scale. We were quite concerned about the tiles

(obviously) and had to see if a) they would work and b) how precisely

would they have to be installed. We did thin skin thermocouple tests and

phase change paint tests. That’s special white paint applied to a

special black epoxy model - the paint goes clear at a specific

temperature. Take motion pictures of the paint changing ‘phase’ and you

get temp vs. time = heating rates. We did some IR testing a few years

later (newer technology). These models were really cool. The thin skin

thermocouple model was all stainless steel and had about 1,000 T/Cs all

over just the Orbiter with 1,750 T/Cs over the entire OTS configuration.

The Thermocouples were positioned along the top and bottom fuselage

center lines, along various wing cords (left wing top, right wing

bottom) and specific “hot spots” like the windshield and the OMS pods. I

wrote the test plans, told the model mechanics what configuration to set

up (all flying surfaces were adjustable).

It was really cool seeing the Enterprise on roll-out day. I could see

things on the Orbiter that were a direct result of some of the tests I

was responsible for. But this could be a whole ‘nother story.

At the time, there were actually some supervisors and managers that were

looking ahead to the first Shuttle flight with respect to correlating

flight data to wind tunnel data. The top surface of the wing had a

different type of insulation than the tiles since the heating rates were

significantly lower. But they wanted to be sure they had sufficient

margin and so they called a meeting to discuss ideas for getting some

actual flight data from the top surface of the Orbiter wing during the

first entry. This wasn’t a safety issue. It was more: ‘Can we use easier

to maintain insulation to save maintenance costs and turnaround time?’

I, the kid 2 years out of college, sat in a meeting with the Department

Manager, my Supervisor and the Analysis group Supervisor. There was a lot

of discussion about ways to instrument the top surface of the (real)

wing. Well, I went and opened my mouth and said, “Why don’t you put an

Infa-Red (IR) camera in a pod on top of the vertical tail looking down

on the top surfaces of the fuselage and the wings?” Gee, they didn’t

laugh! They actually listened and discussed it for about 10 minutes.

But, it didn’t sound like they were going to do it. So, to promote my

‘great idea’ I said, “Well, you could also put a visual camera up there

too. It would be great for Public Relations. Wow! A shot of the Orbiter

during re (oops, sorry) entry.”

Silence . . . . glares . . . mumbling . . .That did it. The Manager,

standing up while closing his tablet portfolio, said, “No pod with a

camera and Paul (my Supervisor), talk to this kid about this will ya?”

More glares. Meeting over.

Yikes!

Paul pulled me into his office and s’plained to me that, as he put it,

“We never, ever, ever talk about doing something for ‘PR’.”

“Why?” I asked.

“Because,” he said, “several years ago we lost the XB-70 because of

‘PR’.”

“Huh?” I said with ‘duh’ written all over my face.

“They conjured up a ‘mission’ to fly the XB-70 with all of the other

aircraft in the Air Force inventory that used the same engines to get a

publicity photo for the engine manufacturer. They wanted a ‘tight’

formation for a better picture. An F-104 got too close and it got caught

in the wing tip vortices of the XB-70, rolled across it’s back clipping

off the vertical stabilizers. The XB-70, F-104 and another aircraft went

down killing a few of the pilots. It was decreed to never do anything

like that again.”

“ . . . . . . Oh.”

So, I became interested in the plane and read the few books that were

available. Now I not only love the aircraft but I have a memory – albeit a

faux pas.

The 1/72nd Scale

Contrail Sutcliffe XB-70

|

That is one reason anyway why I decided to brave the huge box and build

the b e a s t. Photo 2 shows the box and most of the contents. I kept

checking the scale – then I remembered taking the photo at Wright Pat –

it is very big!

There were drawings for either version. I chose the zero degrees

dihedral and the nose set in the subsonic position. Large, and I mean

large, sheets of plastic for the main parts, metal landing gear struts

and decals.

Construction

After studying the plans and the various pieces, the nose (or goose

neck) just didn’t look right. Looking head-on, the model looked like a

chipmunk and from the top like a duck. I studied more photos, then the

drawings, then the parts, back and forth and finally decided to make

some “fixes”. I removed the ‘cheek’ and filled with Bondo or putty and

re-contoured each cheek half before removing it from the backing sheet.

There was so much cutting and filling that it was an easy decision to

NOT put in a cockpit (can’t see in the windows in all of the photos

anyway. That’s my story and I’m sticking to it!

Click the thumbnails below

to view larger images:

The gooseneck parts were prepared and glued together. But, the shape

still looked wrong. I studied the plans, studied the parts, studied the

photos, moved ‘Bert’ (my deceased cat) off the plans and

studied them some more. Then I picked up razor saw and hacked off the

bottom (of the goose neck, not Bert) to improve the taper.

After more putty and sand, sand, sand, dunk (water), it looked right.

Click the thumbnails below

to view larger images:

But now what!? The goose neck, when dry fitted to the spine, stuck up

like a . . . well, let’s just say it stuck up. I had to cut a hunk of

the goose neck out keeping the length the same (triangular cut) but

change the angle. I re-glued it, strengthened the inside with scrap

plastic, pucky, sand, sand, sand. Surgery complete! Patient looked like

it would recover nicely!

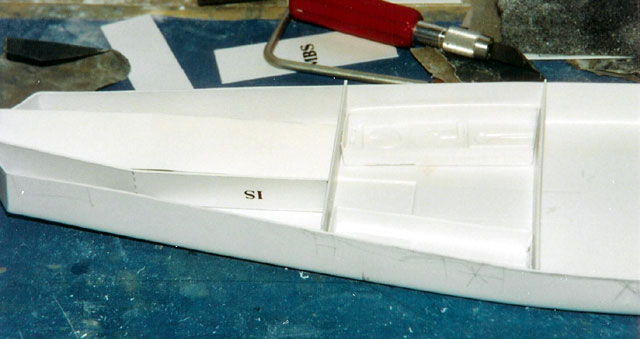

I moved on to the main body (it’s hard for me to call it a fuselage)

that mounts below the wing. These parts fit fine but I had to do lots of

measuring, checking and more measuring, etc to get the gear centerlines

lined up with each other. The dry fit of the main body parts are shown

below. I wasn’t a stickler about the cockpit but I was about the

intake splitter plates. I had to do a little engineering to incorporate

them – even though they too are hard to see.

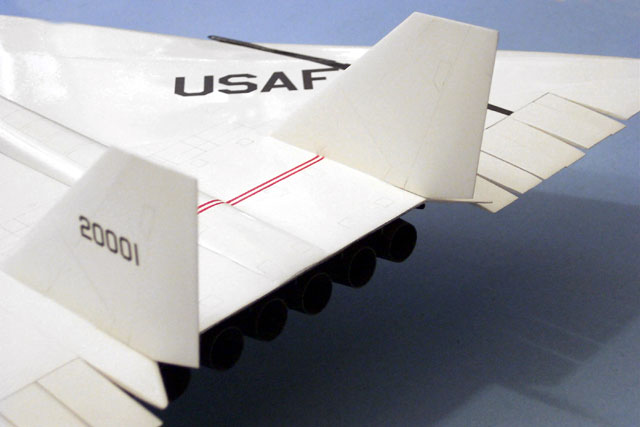

The engine compartment I painted gloss black so you can’t see in past

the exhaust nozzles. The nozzles were made by taking

(stealing) one from another kit on my shelf (sorry, I don’t remember

what kit . .. a jet I think . .. . ! ). Anyway, Mr. Bill Ferrante a San

Jose IPMS member was kind enough to make a mold and cast me 5 more. Well

6 actually, I put the original back into the unknown nozzle-less kit.

Click the thumbnails below

to view larger images:

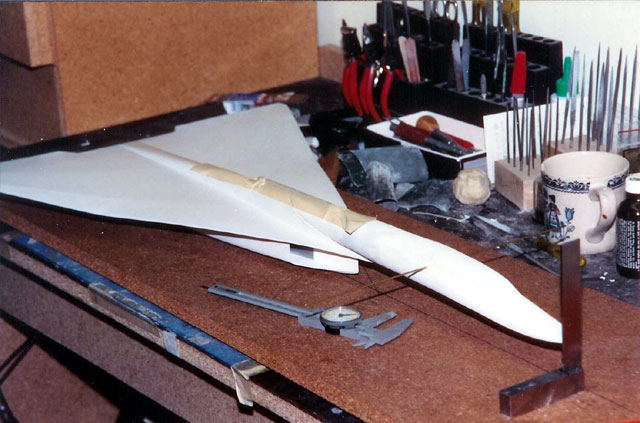

The wing, although big, was relatively easy except I just had to cut out

the “tail feathers” and glue them as seen in the photos that I had – all

different angles. The body was aligned and glued to the

wing. Matching centerlines and getting the wing level wasn’t too bad.

Click the thumbnails below

to view larger images:

While the glue was drying, I would tackle the landing gear. I spent more

time sizing metal tubing and wheels until I got the correct combinations

. . . or close enough.

Now, the real fun began – attaching the goose neck to the spine which is

attached to the top of the wing. But wait a minute.

The wing has a funny

but noticeable camber effect right at the front of the delta plan form.

This part had to deflect a little to make it right, but the spine, right

where the goose neck is to be glued, was a terrific stiffener. I had to

make three cuts in the spine to match, or come close, to the

correct contour of wing/intake. The wing has a funny

but noticeable camber effect right at the front of the delta plan form.

This part had to deflect a little to make it right, but the spine, right

where the goose neck is to be glued, was a terrific stiffener. I had to

make three cuts in the spine to match, or come close, to the

correct contour of wing/intake.

The goose neck was supposed to be attached with a single sheet of

plastic as a spar, but I beefed it up. I did not want that joint to

fail! A thicker piece of plastic glued with plastic cement plus Two Ton

epoxy – that should hold it! Now it’s as strong as an ax handle!! The

main body/wing section was placed on a piece of particle board (flat). I

used a triangle, right angle tool, my eye, a boy scout compass, smoke,

mirrors – anything I could find to help me line up the goose neck (6

degrees of freedom) with the main body (6 degrees of freedom). This took

two evenings before I was satisfied. I held my breath and glued it

hoping it wouldn’t sag or turn after the clay props and tape were

removed. It didn’t!

I replaced the kit vertical stabilizers and canards with sheet plastic.

First to be more scale like (thinner), 2nd only one piece and, 3rd

flatter and harder plastic. I added brass dowel pins for a firm joint.

Finding and making the holes so everything lined up was a challenge. I

had to move my plans guard, Bert, to consult the plans frequently. Some

times he didn’t like that. The first thumbnail below is Bert’s version of Clint Eastwood,

“So you think you’re gonna move me . . .Huh, punk . . . .Go ahead . . .

. make my day!” The next thumbnail shows the intake area and some of the gooseneck

to main body joint. Not quite done with sanding but getting there. P I

sanded the entire aircraft with 600 wet. I felt like I was sanding the

Golden Gate bridge! The final photos shows the model just before painting.

Click the thumbnails below

to view larger images:

I hosed on Floquil Reefer White + Crystal Cote and wet sanded with 1000

wet paper between each of the four coats. Sand, sand, sand, dunk . . .

remember . . ? I over-coated with pure Crystal Coat, put on the decals

and some pencil panel lines. (I do not suggest doing pencil lines. I

think it’s the only thing on the model I’d change.) I added another coat

of Crystal Cote, the gears, doors, pitot, engines, a couple of blade

antennas – done!

Even after all of the ‘fixes’ this is, no doubt my favorite airplane and

my favorite model.

As I look at these assembly photos I first of all

applaud Contrail Sutcliffe for even coming out with the kit, but with

all due respect to them and at the risk of sounding immodest, I feel

that on this one, I truly turned CRAP 2 CAKE... but, that’s what vacuforming

is all about!

Click on the thumbnails

below to view larger images:

Model, Images and Text Copyright © 2003 by

Bill Dye

Page Created 05 March, 2003

Last Updated 17 March, 2004

Back to HyperScale

Main Page

|

Home |

What's New |

Features |

Gallery |

Reviews |

Reference |

Forum |

Search