|

Albatros D.III

by

Tony Bell

|

|

|

Albatros D.III |

Eduard's 1/48 scale Albatros D.III is

available online from Squadron

After the end of the “Fokker

Scourge” in late 1915 by the Allied DH.2’s and Nieuport 17’s, it wasn’t

until the Albatros fighters were introduced over the Western front in

mid-1916 that the Central Powers’ were able to re-established their

superiority in the air.

The D.III was introduced in

early 1917. In an attempt to improve manerverability, the D.III emulated

the sesqui-plane design of the Nieuport fighters with a lower wing that

was little more than half the area of the top wing. This had the desired

effect on performance, but unfortunately it also suffered from the same

structural limitations as the Nieuport. Due to their single spar design,

the lower wings were notoriously prone to twisting and separating in a

dive, resulting in catastrophic failure.

The Albatros D.V inherited

the same weakness, and it wasn’t until D.Va that the structural problems

were addressed. By the time of it’s introduction however, its performance

was no match for the Allied Spad XIII, Camel or SE5a. It wasn’t until the

Fokker D.VII came along that the Germans were able to field a fighter that

was demonstrably superior. By then of course, it was too late in the war.

The Kit

Having my interest in WWI

sparked by a fellow IPMS Toronto member, I decided to pick up the Eduard

Albatros D.III at a local show. I got the non-Profipack early version of

the D.III, featuring Manfred Von Richthofen’s machine on the box top. The

parts are moulded in a medium grey styrene, as opposed to the tan plastic

used for Eduard’s more recent releases. The parts breakdown is

conventional, featuring two fuselage halves, separate lower sesqui-wings

and a single piece upper wing. The surface detail is very crisp, and the

trailing edges of the wings are razor sharp. While the rib tapes are not

represented, the fabric effect on the wings and tail surfaces is nicely

restrained.

The decals are printed by

Aeromaster and are in perfect register. The white areas are a bit thick,

but very opaque.

I decided to pick up

Eduard’s photoetch set for the D.III, mainly for the Spandau’s cooling

jackets. The set also features replacement vents and hatches for the

fuselage, elevator control horns, radiators and radiator flaps, amongst

other details. The set is a significant improvement over an already nice

kit.

Both engine and cockpit have

to be assembled before closing the fuselage, so I decided to break with

tradition and start with…

The Engine

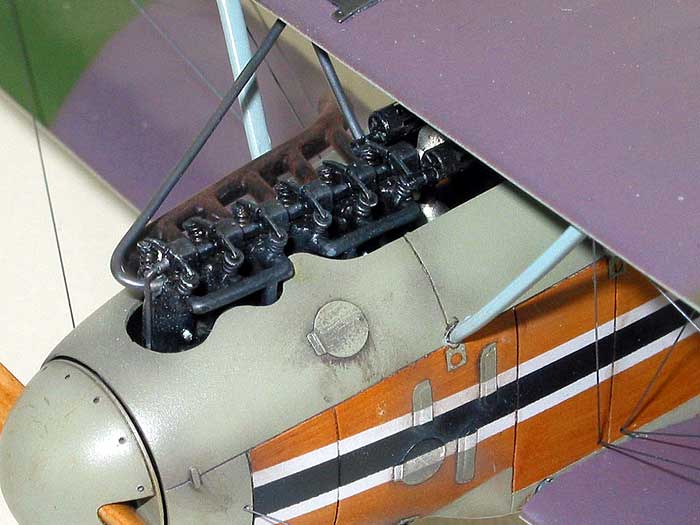

The kit engine is a very

nice representation of the 160 hp Mercedes inline six. The only things

lacking are the rather prominent valve springs and rocker arms. Each

spring was fabricated from fine wire wrapped around a No. 75 drill bit.

They were cut to length, superglued to the engine and topped with disks of

sheet styrene punched with a Reheat Punch & Die set.

Click the thumbnails below to view larger

images:

The rocker arms were made

from 0.010” styrene strip. I also added spark plug wires, but would not do

so again, as they are completely invisible inside the fuselage.

The engine was airbrushed

Tamiya semi-gloss black, and then drybrushed with Humbrol Metalcote Steel.

The crank case (also totally obscured) was painted with Alclad II White

Aluminum.

The Cockpit

After finishing the engine,

I turned my attention to the cockpit. This was a relatively risk-free area

to experiment with painting wood grain. I started by spraying the fuselage

interior with a 1:1 mix of Tamiya buff and white. Once this was dry, I

brush painted Windsor & Newton Raw Sienna artist’s oil all over the

interior, spreading it thinly and evenly. Too red. I wiped it all away

with paint thinner and tried again with Yellow Ochre. Too orange. I wiped

it clean again and tried a mix of Burnt Sienna, Yellow Ochre and Raw Umber

in an approximate ratio of 1:1:2. Aaah, that looked better.

Once I had brushed the paint

on thin enough to get the right colour density, I took a clean, absolutely

dry, paint brush and dragged it over the oil paint, leaving wood grain

streaks. I joggled (is that a real word?) the brush to give the grain a

bit of variation. As the brush picked up the paint, I wiped it off on a

clean, lint free cloth. Lint free is the key phrase, as any speck of lint

will glom (again, a real word?) onto the oil paint and mar the finish.

Once I was satisfied with the look of the wood grain, I set the pieces

aside for at least a week to dry, after which I sprayed on a coat of

Polyscale satin to protect the finish.

The other wood cockpit

pieces were painted the same way. Once all the wood was painted and

sealed, I brush painted the cockpit stringers with Testors burnt sienna

enamel.

The photoetch set offers a

replacement seat, but the real Albatros had a leather covered plywood

seat, which sheet brass was just too thin to represent. I opted to use the

kit seat, with a cushion cut from 0.020” sheet plastic. The whole seat was

roughed up with 120 grit sand paper and brushed with liquid cement to

simulate the leather texture and painted semi gloss black. The etched seat

harness was painted buff, suitably scrumpled and draped and attached with

white glue. The control column was dressed up with photoetch parts and

attached at a left bank, nose down angle. The rudder bar was also attached

at an offset angle.

Click the thumbnails below to view larger

images:

The sole instrument in the

Albatros cockpit is the tachometer. The kit supplies a blank face, and

there is nothing in the etched set. Having seen Mark Miller’s amazing 3D

computer renderings of the Albatros D.V on the World War I Modelling Page,

(

http://www.wwi-models.org/Images/Miller/render/Albatros/index.html ),

I emailed him and asked for the image that he used for the tach. He was

kind enough to send me the file, which I printed on my bubble jet and

photo reduced to scale. I then punched the gauge face out, attached it

with epoxy and finished it off with a Reheat instrument bezel.

The photoetch set also

offers various replacement switches and handles and whatnot which were all

used. The cockpit details were painted with black, silver and RLM02 grey.

The Fuselage

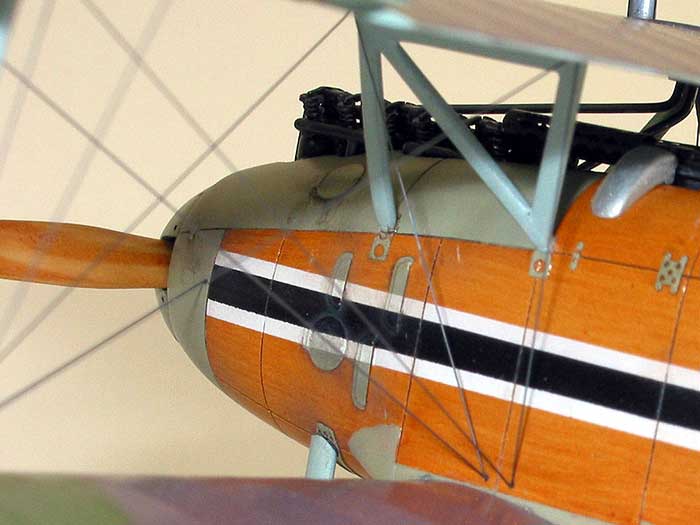

I decided to tackle the

Spandau machine guns first. The muzzles were drilled out and cut off, and

the cooling jackets were removed and discarded. The photoetch set provides

replacement cooling jackets which have to be formed into cylinders. This

was done by wrapping the etched pieces around an appropriately sized drill

bit. A section of hypodermic tubing was superglued inside the jacket along

the seam and attached to the kit plastic breech. The business end of the

cooling jacket was capped with the appropriate etched piece and the

plastic muzzle glued on. The etched set also provides cocking handles

which were superglued on.

The assembled guns were

first airbrushed with a satin blue-black mixed from Tamiya paints and then

heavily drybrushed with Humbrol Metalcote Gunmetal, followed by a lighter

drybrushing of Metalcote Steel. I then set guns aside until the fuselage

was finished.

On the real thing, the

spinner was slightly smaller in diameter than the fuselage, allowing the

edge of the cowling to be seen. I cut away the spinner backing portions of

the fuselage halves and thinned the edges down by scraping and sanding

them until they were acceptably sharp. The two rigging attachment points

at the root of each lower wing were drilled out with a No. 80 bit.

The cockpit and engine were

dry fitted and, much to my surprise, I found that there was no adjustment

necessary. The fuselage halves were joined with superglue, and the seams

were eliminated with a light sanding. The ventilation louvers, access

covers and foot step on the sides and bottom of the fuselage were scraped

and sanded away, as the photoetch set provides replacements. I cut the

rudder away from the vertical fin and attached it at an offset. The

horizontal stabilizer was glued to the fuselage to get it aligned properly

and once dry, the elevator was removed and repositioned. The etch set

provides the elevator control horns which were attached with superglue.

I decided to paint the

fuselage before attaching the wings in order to simplify the process.

After masking the engine and cockpit with tape and tissue paper, the sheet

metal portions of the forward fuselage were sprayed with Aeromaster enamel

RLM02 grey and masked off. The wood portion was painted as described above

and left to dry for a week, after which I sprayed on several coats of

Future to protect the finish.

The etched replacement

louvers and access covers were formed to the contours of the fuselage by

gently rolling an X-acto handle over them. They were painted RLM02 and

attached by brushing a dab of Future on the fuselage and positioning the

etched part, much like applying decals. Once in position, more Future was

brushed around the edges and allowed to dry.

The tail surfaces were

masked off and painted Tamiya flat white. The fuselage striping were then

masked and painted white, masked again and painted black. I then removed

all the masking and sprayed the whole fuselage with yet another coat of

Future. Finally I removed the cockpit and engine masking and brush painted

the coaming with Testors Leather enamel.

The Wings

The wings were prepared by

pre-drilling the holes for the rigging with a No. 80 bit in a pin vise.

The anchor holes in the top wing were drilled only part of the way through

whereas the holes in the lower wings went all the way through. The

radiator on the upper wing was scraped and sanded away in favour of the

etched replacement.

I cut the ailerons away from

the upper wing and reattached them to match the position of the control

column and the hinge straps replaced with 0.005” styrene strips.

The bottoms of the wings

were sprayed with Aeromaster enamel RLM65 lightened with white. For the

upper surface mauve I mixed Tamiya flat red, blue and white, while the

green was a mix of Polly Scale RLM83 Lichtgrun and RAF Slate Grey. The

colour mixing was totally unscientific, the paints being blended until

they simply “looked right.” The wings were sprayed with Future to prepare

them for the decals later on. The bottoms of the wings

were sprayed with Aeromaster enamel RLM65 lightened with white. For the

upper surface mauve I mixed Tamiya flat red, blue and white, while the

green was a mix of Polly Scale RLM83 Lichtgrun and RAF Slate Grey. The

colour mixing was totally unscientific, the paints being blended until

they simply “looked right.” The wings were sprayed with Future to prepare

them for the decals later on.

After painting, the

photoetched radiator parts were attached to the upper wing with contact

cement, and the radiator louvers glued in place with superglue. The louver

handle was built up with superglue and painted buff.

Assembly and Rigging

As is the case with Eduard’s

earlier kits, the locating holes for such things as the lower wings and

struts are really only dimples that need to be drilled out. I did so and

attached the cabane struts to the fuselage, using the upper wing to

position them properly. Once these were set, I attached the interplane

struts to the upper wing and attached the wing to the cabane struts. Once

this had set, I finally attached the lower wings to the fuselage and

interplane struts, letting the struts set the proper dihedral.

Then when I was handling the

model, I applied a leetle too much pressure and collapsed the

entire wing assembly.

After much swearing and

gnashing of teeth, I did what I should have done in the first place and

drilled out all the mounting points for the wings and struts and inserted

lengths of steel wire to hold it all in place. I went through the same

sequence all over again and was rewarded with a nice strong wing assembly.

The rigging was accomplished

with “invisible” nylon monofilament thread which was painted with Humbrol

Steel (can you tell I like this paint?). Several feet of thread were

painted all at once in order to provide ample rigging material. Each piece

of rigging was cut to about twice the required length and fixed in the

anchor hole in the top wing with superglue. Some holes were intended for

two pieces of rigging, so these were glued simultaneously. Working from

inboard to outboard, each piece of rigging was then pulled through it’s

proper lower hole, held tight and fixed in place with superglue applied

with a length of stretched sprue. A self-locking haemostat used to pull

the thread tight was an invaluable tool during this exercise. Once the

glue had set up, the excess rigging was carefully trimmed away with a

fresh scalpel blade and touched up with paint.

The rigging was completed by

attaching small lengths of painted thread to the elevator control horns.

Adding the Details

Having learned from my

earlier mistake when attaching the wings and struts, I drilled and pinned

the landing gear struts to the fuselage. The strut brace and axle were

replaced with brass tubing and styrene rod, respectively. This was done

simply because it was easier than cleaning up the kit parts rather than

for strength. Some cotton thread was de-fuzzed by passing it quickly over

a candle and wrapped around the axle and struts to simulate the bungee

cord shocks.

I painted the prop in a

similar manner to the other wood areas, and simulated the laminations by

removing more oil paint from the lighter areas with a fine brush slightly

moistened with thinner. The prop was given numerous coats of Future give

it a high gloss varnished look. The spinner was modified by drilling out

the fasteners around the circumference.

The open forward end of the

fuselage was filled with a black painted disk of sheet styrene set back

about 1mm from the forward edge. The prop and spinner were then glued to

this with a 0.030” styrene spacer.

The coolant pipes that run from the engine to the wing radiator were

fashioned from fine solder and attached with superglue. These were painted

steel in situ and buffed lightly.

The only decals used on this

model were the propeller logos and the national crosses on the wings,

fuselage and tail, for which I used the kit decals. It was when I was

applying the upper wing crosses that my second setback occurred.

The fuselage and tail

crosses went on fine, but I discovered that the kit decals just sneered at

Gunze Mr. Mark Softener and at Microset. The only thing these decals would

respond to was Solvaset so that’s what I used from the outset when

applying the crosses to the wings. The first decal went on just fine. By

luck, I managed to position it exactly right off the backing paper and did

not have to slide it into position. The second decal didn’t go so well.

It’s initial position was a bit off, but when I tried to prod it into the

right place I discovered that the Solvaset had softened the Future and

effectively turned it into contact cement! I tried to lift the decal off,

but only succeeded in mangling the decal and ruining the paint finish.

More swearing and gnashing of teeth!

I let the now-wrecked area

of the wing re-harden whereupon I sanded it down and repainted the green.

When I reapplied the Future something strange happened and it went all

fish-eyed and horribly uneven. Even more swearing and gnashing of teeth,

but with a much heavier emphasis on the swearing! Out came the sandpaper

again. And the green. And the Future. This time I cut it with a bit of

Tamiya thinner and it sprayed beautifully. I managed to beg a friend for a

replacement decal and finally applied it properly, using the Solvaset only

on top of the decal.

The canvas and metal

surfaces of the airplane were sprayed with a 60/40 mixture of Poly Scale

flat and satin to give it a slight sheen.

Weathering was kept light

and consisted of an artist’s oils wash mixed from Burnt Umber, Lamp Black

and Titanium White. A similar brownish grey was mixed from Tamiya paints

and sprayed heavily thinned in various areas to reproduce general grime.

Finally the mud on the tires was made from ground pastel chalks mixed with

water and applied with a Q-tip (cotton bud).

The exhaust was painted flat

black and dusted with brown and orange chalk pastel powder.

As my first ever attempt at

a WWI subject this was a definite learning experience. Rigging and wood

graining in particular required techniques that I had never tried before.

The Eduard Albatros was the

perfect kit in this circumstance, being both well engineered and nicely

detailed without being overly complicated (imagine a Bristol Fighter or

Fe.2b as a first crack at a WWI model!).

It may have been my first,

but it won’t be my last.

Click the

thumbnails below to view larger images:

Model, Images and Text Copyright ©

2003 by Tony Bell

Page Created 04 March, 2003

Last Updated

17 March, 2004

Back to

HyperScale Main Page |

Home |

What's New |

Features |

Gallery |

Reviews |

Reference |

Forum |

Search